Folks, I have a confession to make.

I’m a sucker for good self-help books.

Therefore, when self-help author “gurus” want to illustrate the dangers of head-in-the-sand thinking, by quoting some of the most inaccurate predictions in history, I’m all in.

For example; did you know that the chairman of IBM once claimed there’d be a world market for “maybe five computers”? Or that an internal memo at the telegraph company Western Union concluded that this “telephone” thing has too many shortcomings to ever be “considered a serious means of communication”? And let’s not forget Bill Gates’ famous old blooper,”640 kilobytes ought to be enough for anyone!”.

Now, sure, some people actually claim that these quotes are either ripped out of context or simply fake, but that’s another story. See, dodgy anecdotes are to motivational literature what facts are to science, and in these above cases the point being made is a pretty important one: in life, inflexible ideas and mindsets about the ‘right way’ to do things can be a serious obstacle to doing them the optimal way.

Which, when you think about it, has a fascinating implication:

If knowledge – about the right way to do stuff – can be a bad thing… might it make sense to think of ignorance as a precious resource, worth protecting?

The Japanese surely think so, because they’ve even got a name for it.

Shoshin.

The beginners mind.

Valued highly among other famous samurai-style states of mind like fudoshin (immovable mind), mushin (empty mind), zanshin (lingering mind) and more.

Now, if the concept of a beginners mind, shoshin, sounds like a brainless championing of stupidity, take a sec to just consider it mathematically: compared to the universe of your ignorance, the terrain of your knowledge is maybe the size of the Vatican (the world’s smallest country). And logically, whats the actual chances that all the good stuff, that tasty knowledge juice, is located within the borders of the Vatican?

That’s right.

Slim.

I guess it’s like I read in the Harvard Business Review a while back:

“Most of us will cheerfully acknowledge our ignorance about plenty of things… but few of us would dare cultivate a healthy ignorance within our own fields of endeavour”

– David Gray

Shoshin, the beginners mind, tells us that ignorance – being the opposite of knowledge (which is infinitely reusable) – is almost a one-shot deal: once it has been replaced by knowledge, it can be hard to get back. Hence, we must strive to always keep the beginners mind – because after it’s gone we are more likely to follow the usual, well-worn paths to find answers; keeping within the borders of our own imaginary Vatican.

Solved problems tend to stay solved – sometimes catastrophically so.

So let me try to widen the borders of your knowledge domain today, by educating you about something I find really cool. Because this post is neither about new-agey self-help advice nor Japanese samurai concepts.

It’s about something completely else.

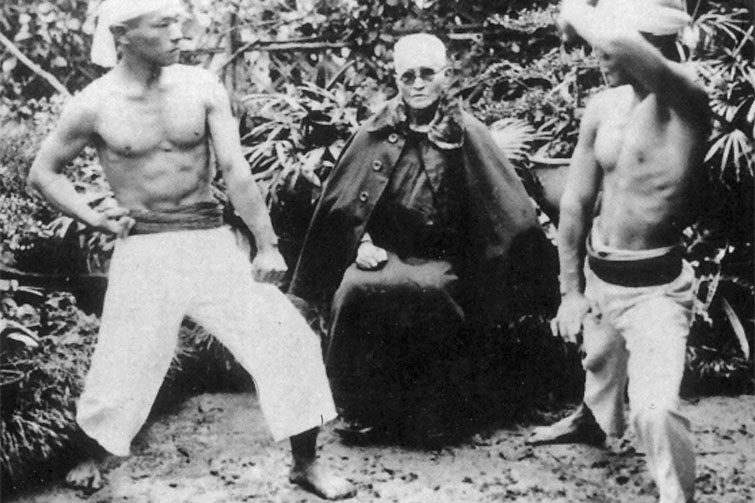

About a seemingly lost skill of old-school Karate, today only practised by true Okinawan Karate aficionados.

Called…

(ready?)

Meotode.

The original Okinawan way of posturing, blocking and striking.

See, today’s concept of blocking with one hand, then countering with the other hand (while always keeping the passive hand safely chambered at the hip) was not the way to go back in the days. You know, the days when the success rate of blocking an enemy’s strike strongly correlated to the success rate of yourself waking up tomorrow.

Old-school, Okinawan no-nonsense Karate was grimey, dirty, raw and unfair. There was – unlike our modern one-, two-, three-step sparring (yakusoku or ippon/nihon/sanbon kumite) – no room to let your opponent patiently stand in a picture-perfect zenkutsu dachi to wait for your deadly “one shot kill” counter punch to his/her abs. There was – unlike our modern, free, dojo/tournament sparring (jiyu kumite) – no safe spot several feet away from where to judge an enemy’s posture, size, possibility of concealed weapons and strengths; before safely engaging him/her in a playful game of tag modern “Karate” fight.

Okinawa, the birthplace of Karate and still the poorest prefecture in all of Japan, was a place where you didn’t want to spend too many minutes in the wrong parts of town. Which means that original Okinawan Karate – the kind still advocated by only a few true old-school grandmasters of the last generation – was all about engineering an idiot-proof way of dealing with vicious thugs and sneaky hoodrats coming your way as quickly as possible.

Enter meotode.

Meotode, literally meaning “husband and wife hands” in uchinaaguchi (the native Okinawan language) was a way of maximizing ones strategical advantage in a physical altercation by utilizing both arms equally in continuously attacking and blocking – while keeping your vital bodyparts safely out of the firing line, using the optimal footwork/body movements of tenshin, taisabaki and irimi.

Meotode is a concept, theory and principle but also a technique.

However, before we go any further with this, let’s just agree that Okinawan Karate was never about killing people – contrary to what some people would like to have you believe. The island was way too small (and peoples’ families were way too big!) to have a whole army of revengeful relatives chasing you down. Dropping somebody dead was an exception, never the norm. Yet some Westerners, who have probably read way too many samurai novels to pass a sanity test, seem to think otherwise.

But I digress.

So, what does this “meotode” stuff look like anyway?

Must be pretty awesome considering I have barely cracked a joke in this whole article, right?

Well, that’s simply because it’s a pretty boring posture, to be perfectly honest. I mean, look at it, it doesn’t even come close to the crane stance!

Here:

“But, but… hey, hold on a sec Jesse-san!” I hear you going.

“That looks exactly like a regular double block (morote-uke), doesn’t it?!”

Indeed it does. As featured in a plethora of kata, including Pinan Shodan/Yondan/Godan (Heian), Jion, Pachu, Seisan, Sanseiru, Niseishi (Ryuei-ryu), and many other kata (sometimes in slightly different forms, considering hand placement and rotation though).

But here’s the kicker:

We might call it a morote-uke (uke = block) in today’s terms, but if we are to go back to the source, in reality it’s not actually just a block.

In fact, it’s not even an attack.

It’s both.

The thing is, in the meotode posture (what we generally refer to as “kamae”) you never have a passive or active hand (what the old masters referred to as a “dead hand”). While we, today, are accustomed to always blocking with the front hand and counter striking with the back hand, this was certainly not the purpose in using meotode, as the front hand could actively switch between blocking and attacking in an instant, just as well as the rear hand could jam, strike or grab at any time it was strategically appropriate to do so.

No rules, no form, just pure efficiency.

Maximizing the possibilities of successfully landing the first shot (following it up with a flurry of more shots) while minimizing the amount of openings presented to an opponent by continuously occupying the centerline.

That, was the sweet purpose of meotode.

So how the heck is meotode actually used then?

I’m glad you asked.

My answer is: in a number of ways, depending on the situation.

But of course I know that’s not what you wanted to hear, so I have called upon my two loyal slave… umm… “students” Douglas and Jesper to demonstrate one of the real hidden beauties of meotode.

But first, think about this: How does one block and attack with the same arm without losing power and speed? I mean, a good hard block will always stop your arm dead in its tracks (which is why most people use the chambered arm for the follow-up attack), right? Surely, you can’t possibly attack with the leading, blocking arm from such a short distance and expect to have any significant power behind the punch, can you?

Well, perhaps not.

Unless…

You block and attack in the same motion.

So, here’s three of my favorite examples of meotode style blocking + attacking with the front hand. These following exercises were actually handed down directly from Nakama Chozo (1899-1982), perhaps one of the most unknown true masters of Okinawan Karate:

#1:

#2:

#3:

So now you know both why the Shotokan kata Empi has those weird “flying swallow” punches (#1), as well as why all these super old Okinawan senseis often seem to have such a “sloppy” technique in their kata demonstrations. It’s not that they haven’t taken their pills that day, but that some of their kata were designed for meotode, meaning you will need to punch with your elbows out to the sides (#1 and #2), or elbow bent down (#3) and generally change the path of the strike (like in #1: think age-zuki) for the technique to actually work correctly in both blocking and attacking!

Imagine that. A sensei telling you to punch with your elbows pointing more out to the sides. Sounds like heaven…

But – would that get you past the first round of any modern WKF kata tournament?

Nope.

Then again, meotode wasn’t designed for that.

So, lastly, should we all stop practising our finely tuned streamlined modern Karate punching and resort to the crude simultaneous block/punch methods of old hardcore Okinawan Karate? Should we try adopting the beginners mind (shoshin) and mix some of our plain vanilla Karate up with some of that wacky stuff which might be situated outside of our precious comfort zone? Outside of our imaginary Vatican state of knowledge? Huh?

Perhaps we should.

Or perhaps we shouldn’t.

Or perhaps I just don’t know what I’m talking about.

In which case, I suppose, what I’ve got to say might be particularly valuable.

Go figure.

33 Comments