Question:

Do you know the difference between Okinawan Karate & Japanese Karate?

I didn’t.

Until I visited Okinawa – the birthplace of Karate.

Wow!

Since then, I’ve revisited the amazing island over a dozen times. I even lived there in 2009, studying Japanese at Okinawa University.

So I can assure you…

There are MANY differences between Okinawan and Japanese Karate.

Check it out:

#1. Higher Stances

Okinawan Karate has a lot of high stances.

Why?

Because it’s natural.

For many people, this is good news!

Deep Karate stances can often feel “forced”, especially for tall Westerners, and tend to be painful for knees/feet/back.

(Particularly if done wrong.)

To put things into perspective, an Okinawan zenkutsu-dachi can be half the length of a Japanese one.

Perfect for lazy bastards like me!

But…

Will these kinds of high stances build leg strength and stamina?

Not really.

That’s not the point either.

The stances of Okinawan Karate are meant to be practical when applied in self-defense, since they can be quickly and effortlessly reached from your everyday stance.

That’s the point.

#2. “Why” Over “How”

If you practice Karate in Okinawa, you will often hear the word “imi”.

“Imi” translates to “meaning” in English.

Hence, in Okinawan Karate, the meaning of a technique is often more stressed than how the technique is actually executed.

The Why is more important than the How.

Japanese Karate, on the other hand, is often more focused on the How rather than the Why.

How come?

There are three main reasons for this:

- The meaning of many techniques was lost during the historical transmission of Karate from Okinawa to Japan. If you don’t know the Why, it’s more sensible to teach the How.

- The purpose of Japanese Karate is not aligned with the purpose of Okinawan Karate anymore. Historically speaking, Japanese Karate was molded to suit the spiritual Way (“Karate-Do”) of contemporary martial arts like Judo, Kendo, Aikido etc., with the main purpose of developing the character of its participants (through the How). The purpose of Okinawan Karate has always been mainly self-defense oriented (the Why).

- The level of martial knowledge , i.e. biomechanics of Budo, is much deeper in Japan. Many techniques of Japanese Karate are influenced by other, more established, Japanese martial arts where the optimal movement patterns are well-researched.

For example, a Japanese sensei will go very deep in details of a kata.

(How to twist your hips, how to adjust your feet, how to shift your weight etc.)

But an Okinawan sensei will often remind you of the purpose of a kata instead.

The “bunkai”.

Get it?

#3. No “Osu! / Oss!”

In Japanese Karate, the verbal command “Osu!” (pronounced “Oss!”) is used sometimes.

In Japanese Karate, the verbal command “Osu!” (pronounced “Oss!”) is used sometimes.

This phenomenon has also spread to the West, and is even getting popular in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and MMA too.

But…

I’ve NEVER heard the term “Osu! / Oss!” being used in Okinawa.

Why?

The reason can be found here:

The Meaning of “Osu” / “Oss” (+ When You Should NEVER Say It)

Okinawans generally use the word “Hai!”

#4. It’s Not a Sport. It’s a Lifestyle.

When Karate was introduced to Japan, many things changed.

For instance, people started competing.

Most people don’t know this, but Japanese Karate practitioners actually changed many kata and added tons of new kumite techniques, for the sole purpose of scoring points in competitions.

Trust me; you’ll never see an Okinawan sensei teach you a spinning hook kick to the head!

Don’t get me wrong though; people in Okinawa compete too these days. But there’s a big difference in their approach.

In Okinawan, Karate is not a sport.

It’s a lifestyle.

Like one of my Okinawan friends, a 7th dan Shorin-ryu sensei, once told me:

“Karate is part of our cultural identity”.

It truly is.

Karate’s heritage is everywhere in Okinawa, and it’s such a natural part of their culture that it simply makes no sense to compete in it.

A growing bamboo does not compete with the bamboo next to it.

Right?

#5. Chinkuchi Over Kime

In Japanese Karate, the concept of “kime” is super important.

In Japanese Karate, the concept of “kime” is super important.

You’ve probably heard the term.

The word “kime” comes from the root “kimeru”, which literally means “to decide” or “to fix”.

Kime signifies that instant stop at the end of your technique.

(Read more: What is “Kime”? Dr. Lucio Maurino (World Karate Champion) Explains & Demonstrates)

Now check this out…

In Okinawan Karate, there is something else:

Chinkuchi!

You see, in Okinawan Karate it’s not important to freeze the technique quickly.

It’s more important to transfer all of your energy into the opponent – like a shockwave. To do this, you need an explosive release of full-body power.

Have you ever seen the famous “one-inch punch” by Bruce Lee?

It’s a perfect example of chinkuchi.

(Read more: Chinkuchi – Another Exotic Okinawan Karate Word)

It’s all about power.

#6. Kobudo Weapons

Japanese Karate is mostly empty-handed.

But in Okinawa, almost every dojo has weapons on the wall.

Why?

Because they practice Kobudo – the art of handling Karate’s ancient combat tools.

The most common Kobudo weapons are:

- bo

- sai

- tonfa

- nunchaku

- kama

- timbe/rochin

- tekko

- kuwa

- sansetsu kon

- nunti bo

Now, I’m not saying Okinawan Karate is an art with weapons.

But a long time ago, rural Okinawa was a very dangerous place.

Most thugs carried weapons.

And if you’ve never practiced with weapons, it’s hard to defend against one.

Therefore, old-school Karate masters were also masters of Kobudo.

(Related reading: Exposing The Lost Secret of Matsumura’s Mysterious Bo Staff)

Like Nakamoto Masahiro, 10th dan Okinawan Kobudo, once told me after we finished training in his dojo:

“Karate and Kobudo is like brother and sister. Never separate.”

These days, most Karate dojos in Okinawa practice very little Kobudo.

But trust me – they know something!

In Japanese Karate, it’s practiced even less…

If at all.

#7. Old-School Strength Tools

Okinawan Karate masters always promote physical conditioning.

Because if you’re weak and frail, you simply cannot defend yourself optimally!

So, they developed tons of crazy tools to strengthen & condition their bodies.

This gear is still being used in Okinawan Karate today.

Some of my favorites are:

- Makiwara – a wooden, springy, punch board wrapped in straw. The saying “a dojo without a makiwara is not a dojo” should tell you how important this impact tool is in Okinawa.

- Chi-ishi – a stone weight attached to a short wooden stick, made to be swung around the body to strengthen arms, wrists, hands, core and back.

- Ishi-sashi – a hand-held concrete weight in the shape of a padlock, originally made of stone. It’s used in the same way as a modern kettlebell, but with a Karate twist.

- Nigiri-game – big ceramic jars filled with sand, which you grip around the rim (one in each hand) while walking in different stances to strengthen your grip, wrists, arms, legs and core.

- Tou – a standing bundle of bamboo tied together at the top and bottom. You strike it with your forearms, fingers and elbows (almost like a makiwara) but also with your legs, to condition your shins.

In Japanese Karate, you rarely see these training tools – except the makiwara.

But in Okinawa, you find them in every corner of the dojo.

They are essential.

#8. Tuidi Techniques

Next, we have something called “tuidi”.

While Japanese Karate approaches combat from a long distance range, Okinawan Karate prefers a close range.

Here’s where tuidi comes into play.

Tuidi is the Okinawan method of grabbing, seizing, twisting and dislocating an opponent’s joints.

Quite naturally, this aspect of combat also involves other nasty things like choking, unbalancing, throwing, trapping hands, hitting pressure points and nerve bundles.

These things are rarely taught in regular Japanese Karate classes.

Why?

Because, again, Japanese Karate was heavily influenced by pre-existing martial traditions when it was introduced from Okinawa. The original, short, fighting range was changed to a longer one – and concepts like “maai” (engagement distancing) were borrowed straight from Japanese samurai sword fencing (Kendo).

Therefore, the concept of “tuidi” is not as important in Japanese Karate.

But in Okinawan Karate it’s still being practiced.

A common Okinawan exercise for practicing tuidi is called “kakie” – a sensory flow drill, often called “pushing hands” in the West.

(Related reading: 2 Forgotten (But Deadly) Techniques of Okinawan Karate)

In fact, when you closely examine old-school kata, you will see that the bunkai of the kata movements make much more sense in the close range.

Try it and you will see.

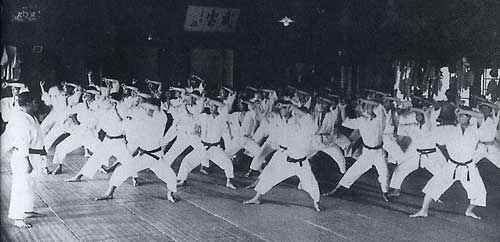

9. Individuals Over Mass Training

As you might have figured out by now, Okinawan Karate has many unique quirks.

To truly understand it, you have to experience it up close.

Basically, you need personal attention directly from a sensei.

This is why Okinawan Karate is hard to teach a big group of people at once – you simply cannot give adequate individual attention to a group of 50 students or more!

Japanese Karate, on the other hand, was tailored for huge groups.

Why?

Because that was the goal when Karate was introduced to the various universities around Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto in the middle of the 20th century.

This phenomenon, along with tournaments, is the reason why many movements of Japanese Karate are bigger and more simplified than Okinawan Karate movements.

They need to be easily seen by huge masses of people!

In Okinawan Karate, it’s the opposite.

In fact, the average Okinawan dojo has room for like 10-15 people. This spartan training environment actually adds to the focus of individualization over mass instruction.

(Read more about training Karate in Okinawa: The Practical Foreigner’s Guide to Training Karate in Okinawa – The Birthplace of Karate)

Sadly, this is the reason many Okinawan masters can’t make a living from Karate.

They don’t have room for enough students.

10. Uchinaa-guchi

Lastly, here’s something you might have noticed throughout the article:

Okinawan Karate has its own language.

“Uchinaa-guchi”.

(Literally: “Okinawan mouth.”)

Many Okinawan Karate terms I’ve mentioned so far – like “chinkuchi” and “tuidi” – are not Japanese words. They are ancient terms of the Okinawan language.

Some other popular ones are:

Muchimi, Gamaku, Meotode, Chinkuchi, Machiwara, Ti, Shinshii, Toudi etc.

(Those of you who attended my seminars will recognise these.)

This language is still used by traditional masters in Okinawa.

For example; when I went to Okinawa last summer, I learnt a new kata called Tomari Chinto. In one particular technique, my sensei told me to have a spring-like upward movement, called “hanchaatii”. Huh? I was clueless! What did he mean? When he saw my confusion, he quickly excused himself and said it in proper Japanese instead; “hana ageru”.

Now I understood!

This goes to show that Uchinaa-guchi is still very much alive today.

But it’s never used in Japanese Karate.

Only in Okinawa.

And with those words I end this list of 10 differences between Okinawan & Japanese Karate.

What do you think?

Of course, these are just generalizations – but they’re based on my personal observations from years of traveling to, and living in, Okinawa and Japan.

Personally, I try to mix the best of both.

Oh, I’d like to mention an 11th one:

The dojo atmosphere.

In Okinawa, you are never afraid of anyone in the dojo!

Nobody tries to hurt you or outwork you, and there is no holier-than-thou aura around the sensei either.

Everyone are there as friends, working together in the spirit of Karate.

It’s a beautiful thing.

Sure, the Okinawan tempo can seem slow compared to the “kill-or-be-killed” tempo in some Japanese dojos – but I blame it on the tropical heat.

(Related reading: The #1 Reason Why Every Serious Karate-ka Needs to Travel to Okinawa Right Now)

In the end, it’s about doing what you love – whether it’s “Okinawan” or “Japanese”.

Makes sense?

Thanks for reading!

166 Comments