Contrary to what some experts will have you believe, the history of Karate is a real puzzle.

At least when you dive below the surface of it.

I mean, loose threads everywhere, strange names and dates that don’t add up, oral testimony that contradicts written “facts” and political bias are just a few of the numerous elements that make the theoretical history of Karate a true pain in the butt when you want to do some good ol’ Karate Nerd™ hobby research (which, for me, is like every day).

Add that to the fact that many history books simply can’t be trusted, even though they might indeed have been written by somebody with an exotic Asian name who loves fried rice and ping-pong (more on that topic here).

See, anybody can write a book.

Or produce a DVD.

(Or write a blog… heh.)

Luckily, we don’t always have to rely merely on written stuff when it comes to exploring the depths of Karate – we have the physical stuff to play with as well! You know, actual combative techniques, stored in our various styles. Kata. Kumite. Kihon. Bunkai. Grappling. Weapons. Real, hands-on, physical fun stuff that surely must be more reliable than dubious books, scrolls and/or ancient proverbs when it comes to understanding the true side(s) of Karate.

Written, theoretical, knowledge of Karate might sometimes be inaccurate; but surely the physical manifestation of Karate’s ancient principles can’t be argued with, can they?

Well…

Unfortunately, they can.

Because, just as there are numerous fallacies in the academical world of Karate (i.e the real birthdate of Matsumura Sokon, the “grandfather of Karate”, anyone?), there are at least as many widespread misconceptions in the practical, applied, world of Karate.

And if you ask me, three of the most common ones are: 1. The withdrawing hand (hiki-te), along with 2. Blocks (uke-waza) and finally 3. Stances (tachi-waza) – which I today plan on briefly outlining for you, dear reader.

See, contrary to what Bruce Lee was known for saying, sometimes a punch is not “just a punch”, so to speak. At least not when we’re talking the wacky martial art of Karate.

Know what I mean?

So, anyways, will you *suddenly* become really awesome at Karate by knowing about these? Yes, probably.

And will your sensei *suddenly* kill you if you should mention these to him/her? Yes, probably.

So, with that being said, and with the utmost discretion, I present to you my 3 Widespread Misconceptions of Modern Karate (That You Need to Know Today).

Let’s go:

#1. The Withdrawing Hand (Hiki-Te)

Assuming you didn’t skip through your high school physics classes, you’ve probably heard about Newton’s Laws of Motion. The third law, perhaps the most famous of the three, tells us that “for every action there is an equal and opposite re-action.” Meaning that for every force there is a reaction force that is equal in size, but opposite in direction.

This is where “hiki-te”, the withdrawing, non-active, hand comes into play.

For every technique you do, you need to pull back the other arm strongly, or else you will be a loser.

Or, at least that’s how conventional Karate wisdom tells us it’s supposed to be...

Have you ever actually thought about why we Karate people always have one hand resting at the hip? Seems terribly impractical, doesn’t it?

I mean, surely we can’t really defend ourselves from such an open and vulnerable position, can we?

Do you see MMA athletes, arguably the hardest fighters on the planet, keeping one hand neatly tucked away at the hip, waiting for that perfect reverse-punch counter window of opportunity?

Hell to the no.

They keep the “passive” hand by the jaw. Or in front of their chest. Or next to their chin. Or somewhere else where it will smoothly allow you to switch between reliable defense and vicious attack.

But look at a Karate fight.

As you execute a technique, whether it’s “one-step”, “two-step”, “three-step” or “free” sparring, in 9 times out of 10 you will pull one hand to the hip as you block, strike or punch your opponent.

Why?

Because that’s how we’ve been taught!

The same goes for kihon (the basics). As we stand in line, waving our arms in the air, repeating endless techniques against imaginary mindless drones, we comfortably keep one hand at the hip for that awesome counter technique we plan on delivering any second now.

If you ask me, somewhere, somehow, people got it terribly wrong.

And it all started from kata.

See, in the original Okinawan kata (which later developed into our modern day kihon and kumite), every movement had a specific reason. If a hand was kept at the hip it was for a specific, highly functional, combative reason. In most cases you were simply grabbing your opponent’s arm, lapel, hair, throat or groin (imagine the bunkai here), pulling it back to your body as you struck him/her with your free hand – maximizing damage (Newton’s Third Law again, remember?) Easy. When this was done solo then, one hand simply pulled back to the hip while the other went forward. But neither hand was inactive, or “resting” on some kind of hip bone. This wasn’t even the norm. In many original Okinawan techniques and kata, both hands were/are often used simultaneously (see more on that topic here) in attacking and defending; what the Japanese nowadays refer to as morote waza (double handed techniques).

Karate was, in one word, highly practical.

Fast forward a couple of decades though, and the norm in Karate is nowadays to always keep one hand at the hip, as we’ve gradually forgot the original intent of most techniques in our never-ending quest for standardizing and simplifying what once was a very applicable and intuitive art of self-defense!

It’s interesting to note that there were still small traces left of the original hiki-te understanding in some 1980’s JKA kumite (watch the KO!):

Cool, huh?

Today though, with new rules and regulations in Karate, the true intent of the withdrawing hand is mostly forgotten (especially in the sporting aspect).

Ask any Okinawan old-school sensei though, and they’ll tell you.

Because they still know.

#2: Blocks (Uke-Waza)

When Bad Breath Tony – your pissed off, jacked up, 300-pound neighborhood Italiano mobster – decides you stole his last slice of pizza yesterday, I bet there’s not much your “impressive” arsenal of various Karate blocks are going to help against his flabby arms.

Why?

Well, let me put it like this: have you ever seen anybody use a traditional Karate block in a fight?

No?

Why not?

Huh?

I’ll tell you why.

Because:

- a) they were never meant for “blocking” (in the fashion we use them today) and…

- b) …if they were actually used for “blocking” the way we do it today, they would totally suck.

- c) (True story.)

Traditionally, what we today refer to as “blocks”, were just various movements that were later interpreted and stylized (then labeled and categorized) as “blocks”, because, hey, that’s what they appear to be!

But everything is not always what it seems (as you bunkai aficionados know).

Using your own limbs to crash into your opponents limbs (modern day blocking) is perfectly fine for young studs in a predictable dojo environment, but far from the optimal way of defending ourselves for us sophisticated people. As Sigismund von Radecki (1898-1970) once wrote: “The power of youth lies in the fact that it enjoys encountering resistance of any kind”. Well, coincidentally enough, modern Japanese Karate was mostly developed by a bunch of Japanese youths!

However, as we’ve already discussed, the original techniques of Karate were meant for another purpose.

Self-defense.

And I don’t know about you, but where I live, in the cold streets of Sweden (literally; it was just snowing in mid-April!), the chances of perfectly timing a traditional block with an opponents attack, in a real “balls-to-the-wall” scenario, is, well, zero. Which is why you never see blocks being used in kumite. And not in self-defense either. Because never, in the history of civil self-protection, has there ever been a mad opponent dashing forward against you, from a classical dojo distance, in a picture-perfect Karate stance, shifting his weight, fixing his hikite, focusing his step straight towards you, being so committed to his course of action that he’s laying all his cards on the table, clumsily giving up all his evil intentions to you – so you can gracefully block his attack and swiftly counterpunch him in the ribs.

It just doesn’t work that way.

Blocks were originally a lot of things. But not what we use them for today. Ever heard the expression “a block is a lock is a blow is a throw”?

Now you have.

And you’re not alone. For instance, here’s a video of my good friend Angel Lemus (who recently started the One Minute Bunkai™ project) showing a very simple, yet effective, basic Okinawan style bunkai combination of a slap, gedan uke (low “block”) and jodan uke (high “block”) against a rear shoulder grab.

Practical stuff.

Because that’s what “blocks” were always meant to be.

Practical.

#3: Stances (Tachi-Waza)

Last but not least, we have this “stances” thingy.

Here’s the deal: Modern Karate is stuck in stances.

Here’s the deal: Modern Karate is stuck in stances.

We treat them like holy artifacts, not to be changed or adjusted, when in fact, they were never something set in stone.

Stances are physical tools to be used, and like with any tool (weapon), the stances have numerous offensive as well as defensive uses. They were not designed for stagnant use, but were (and are) meant to be fluid, ever-changing, depending on your desired outcome at the moment.

Originally, it was just about the distribution of your bodyweight (bend one leg and you instantly get more bodyweight on that leg). For example: In order to maximizing the damage your technique causes by redistributing your bodyweight (mass) in an optimal fashion for maximum power output.

Simple.

So instead of saying:“put your bodymass into that rear elbow strike” a sensei could just rephrase it like: “bend your back leg and sink into the rear elbow strike”. Voila – we have a so called “cat stance”.

Obviously, the various stances were used for a lot more than offensive strikes and attacks; they were used for dodging, shifting, evading, taking down, locking up and breaking down your opponent too.

It all depended on the context (which today has shifted radically).

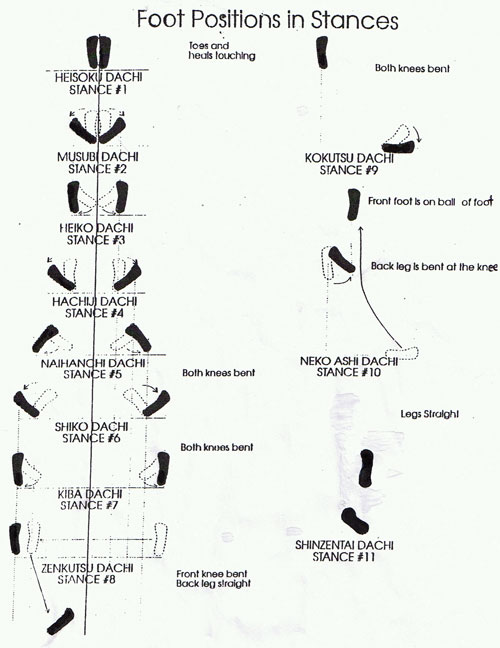

Then… came the modernization of Karate – where organizations like the JKF (Japan Karate Federation) suddenly deems having the feet pointing exactly 45° (shiko dachi), 30° (neko-ashi dachi) or 20° (zenkutsu-dachi) in some random direction is more important than understanding the purpose of the stance to begin with!

Yawn…

This breaking down of, and regimentalization of, the footwork of Karate eventually led to the stagnation of said stances within our treasured kata and kihon (you never find any static stances in kumite, do you?), and here we are today.

By the way, here’s a street fight.

How many stances (transitions) can you count?

(Hint: Press the pause button randomly, and suddenly there’s quite many of them!)

Because stances are meant to be transitional.

End of story.

______________

Right.

So that was some serious stuff many people surely will disagree with.

(Am I wrong or right? Probably both.)

But as you know, that’s fine. In fact, that’s what I like. Sparking new thoughts, drawing new patterns of thinking, creating discussion, questioning established “truths”… it excites me. Not to cause a ruckus, but to see improvement.

And if you don’t agree, well, at least you got what you paid for.

(Nada.)

Because that’s just how we Karate Nerds™ roll.

And with those words I end this humble article on 3 Widespread Misconceptions of Modern Karate (That You Need to Know Today)!

72 Comments