Sometimes it’s tragic how blind obedience and unhealthy “respect” for dogmatic traditions tend to stand in the way for our own improvement in Karate.

As an example of what I mean, here’s what a sharp reader asked me a while back:

I am a swimming coach and master swimmer. Also an intermediate karateka. A few days ago I discovered your site and I am reading your articles. Very interesting! I have a question, if you are so kind to answer: When I surf the web looking for articles about Karate, very few times, if any, I find references to the periodization and planning of karate.

In swimming is very usual to have two or three peaks in a year, and you plan your training with that in mind. Why is it different in Karate? Bompa and Matveev prescribe “undulated” loads within the day, week and month, alternating general excercises with specific ones. Why can’t I find this type of approach in Karate?

Yours truly, Miguel

See what I mean?

If we, to simplify things a bit, treat Karate like any other sport for just a second then it becomes obvious that Karate-ka all over the world are falling behind when it comes to [scientifically] planning their training.

In short, Karate people suck at sports science.

Most of us at least.

Swimming, basketball, tennis, wrestling, golf, badminton, soccer, bodybuilding… you name it. E-V-E-R-Y serious sport that isn’t stuck in the vise of “tradition” (hint: it’s often just a façade for other fundamental issues) uses different means of periodization in their training, to scientifically enhance their skills when it comes to everything from improving technique, explosiveness, strength, mental toughness and endurance to flexibility, agility, speed and practically every other aspect you can come to think of that plays a part in your performance.

So, since I have spent half of my life reading [almost] every book worth reading on sports science, from Bompa to Matveyev to Verkhoshansky, (why do these crazy sports scientists always have equally crazy names?) I thought I might teach you guys some of the basics of sports planning.

Sounds interesting?

Either you’re a part of the problem, or you’re a part of the solution.

Let’s be the solution.

Here’s a brief overview of planning your training, stepping your game up and becoming the best Karate-ka you can be.

[Note: I’m not an expert in any of this, I just pretend to be. I mean, just because I’m a PhD in Awesomeness doesn’t make me a PhD in Neuro-linguistic Programming or Sports Science, mmkay? Free advice is always worth what you pay for it.]

0. Background

Almost every book you read on sports science will have the story about a guy and his bull. The guy’s name was Milo and the bull’s name was…. umm… Bully? Red Bull? Pit Bull? Bull’s Eye.

Almost every book you read on sports science will have the story about a guy and his bull. The guy’s name was Milo and the bull’s name was…. umm… Bully? Red Bull? Pit Bull? Bull’s Eye.

According to popular legend, Milo of Crotona, a kid who wanted to become strong when he grew up, began carrying a young calf on his shoulders each day. The story goes that he would pick the calf up on a daily basis and walk around a large stadium. As the animal grew bigger, Milo also grew stronger. Obviously.

Eventually, after a couple of years of carrying the darn animal every day, young Milo he was able to carry a fully-grown bull!

(Supposedly…)

This is what’s known as “the principle of progressive overload”, and it refers to the idea that you need to increase the demands you impose on your body during your workout routines to make it bigger, stronger, or leaner. Just like Milo. Pretty basic stuff, but important.

For instance, let’s say that you’re following a workout routine (let’s use weight training in this case) designed to help you build muscle size and strength. In theory, all you now need to do is pick an exercise, and choose a resistance you can lift for a certain number of repetitions. Then, as soon as you’re able to increase the number of repetitions, you add a few pounds of weight to the bar. For instance, you might be able to squat 200 pounds for a maximum of 10 repetitions. Add five pounds of weight to the bar each month, and you’d be squatting with 260 pounds just one year from now. Continue the process for the next five years, and the weight you’re using will have risen to 500 pounds.

Soon you’ll be the strongest man alive!

Or, well, not really.

Unfortunately, if you’ve been working out for more than a few months, you’ve probably realized that this kind of continuous progress doesn’t exist. It’s just bogus. A fantasy. Milo of Crotona royally fooled us all, because no matter how hard you train, how many supplements you use, or how much “positive thinking” you do, the principle of gradual progressive overload only works to a certain point.

That point is known as a plateau.

So what do we need to do?

We need to split our training into periods.

This, then, is what’s generally known as “periodization”.

In this article, I’ll briefly explain the concept of linear periodization, since there are many versions of periodization (conjugate, non-linear, reverse linear; with various macro cycles, micro sycles, meso cycles etc.).

Why? Because linear periodization is the “classic” method (originally created by Dr Leonid Matveyev from Eastern Europe) and is easy to understand for everyone.

1. General Preparation Period

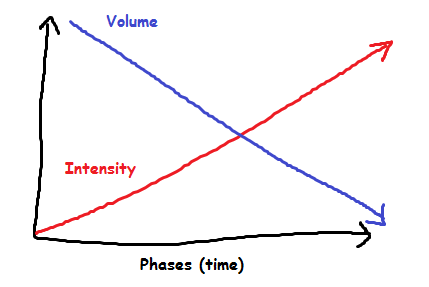

So, the first thing you need to do is to plan a period characterised by a large volume of training, which develops working capacity, general physical preparation and improves technical aspects and basic tactical skills.

This is what we call the GPP (General Preparation Period).

During this phase, feel free to go nuts in the amount of training you do (volume=high) but keep it fairly easy (intensity=low). This is important.

The main focus with the GPP is to develop a high level of physical conditioning to facilitate future training and to protect an athlete’s central nervous system (CNS) from being bombarded with high-intensity training later in the training programme. That athlete is you.

The main objective of this block, the GPP, is to improve your fundament.

In other words, lots and lots of kihon, push-ups, sit-ups, high jumps, kata and kumite. This phase usually lasts from 4 to 12 weeks.

Volume is the key.

Also, when elite athletes say “I practice 6-8 hours a day”, they are generally referring to this period in training. They don’t practice like this always. (I hope!). Just for the record.

2. Special Preparation Period

The Special Preparation Period (SPP) is a transition phase from gross movements to specific sport movements.

The Special Preparation Period (SPP) is a transition phase from gross movements to specific sport movements.

This is where you continue when you’re satisfied with the GPP.

For instance, if you previously did kata, kihon and kumite, along with some extra general physical conditioning stuff, now is the time to focus on the specific thing you need to excel at. Kata for your grading? Kumite for a tournament? Or just general kihon for a grueling seminar in Okinawa later this year? No matter what goal you may have with your training (you do need a goal, you know), here’s where you focus on shifting your training from the general to the specific.

From everything to something.

This phase’s movements are supposed to be specific exercises related to the skills or technical patterns of your goal. To use Kobudo as an example: If you previously practised with all weapons, now is the time to focus on one particular weapon; with the goal of a tournament, grading or demonstration in mind, perhaps?

Improving and perfecting specific technique and tactics (often with the use of various aids) are the main goals of this phase.

Lastly, you basically need to accustom your body to make full use of your increasing motor potential, and execute competition/grading/demo/street fight/whatever-your-goal-is- exercises with progressively greater intensity. In other words, you are now going from high volume to lower volume, while at the same time going from the previously low intensity to higher intensity.

Here, I did a graph:

I know, Picasso ain’t got nothing on me.

3. “Competition” Period

Now, obviously most of you guys don’t compete, but that doesn’t matter.

It’s just called “Competition” Period because most sports have the goal of competing.

In Karate, we might compete too, but it seems most people hate competing for some reason? Go figure. So, your goal might then be something completely else. I don’t know what. But you should know.

Anywho, the main task at this point should be the consolidation of all training factors, which allow you to “compete” successfully in the main “competition” which you’ve been focusing on (and yes, there might be more than one “competition” during this period). This phase is the realisation of all the preparation you’ve done.

During the “Competition” Phase it can generally be said that 90% of the movement/exercise is direct action (related to sport-specific movements), while the other 10% is indirect action (gross motor work/general conditioning).

Your intensity is at this point very high during training (which means you can’t train as often, in order to not die), while your volume is pretty low.

The focus lies in doing brief, but great, work.

It is very important now to allow sufficient recovery (to attain the state of supercompensation. Please, follow the link, it will change your life).

The “Competition” Phase can be several months.

It depends on your schedule.

4. Transition Period.

Okay, so you won the tournament, got the black belt, beat down that old bully from high school, kicked ass in Okinawa, or whatever your general plan was. So what now?

Enter chill mode.

Sort of.

The Transition Phase is, as the name implies, characterised by non-“competitive” activities. This phase is important because while muscular fatigue will disappear in a week or so for most highly trained athletes, CNS (central nervous system) fatigue can remain for a much longer period of time. Therefore, the Transition Phase incorporates rehabilitation (to allow recovery from any injuries), regeneration (including massage, health spas etc.) and psychological relaxation.

Nice…

This phase is often a couple of weeks (1 week if you’re a noob, 3 weeks if you’re a bit better, a month or more if you’re in the UFC or the Olympics). This varies greatly depending on your level, sport and schedule.

Cross-training is highly encouraged during the Transition Period, while your regular training should be cut down to allow your body to recover. However, you can’t chillax too much, since that means you’ll just start sucking more than when you started. Maintain your general fitness level, please.

Keep what you built.

And then start all over again for your new goal.

Which concludes this very brief overview of linear periodization and sports science applied for Karate. There is much more out there, just search and you’ll find. The hard part is, as always, simplifying and adapting.

Don’t let “tradition” be an explanation for acting without thinking.

Be the Karate-ka you were meant to be.

The End.

13 Comments