History is rarely written by losers.

And if the modernization of Karate was a popularity contest, the losers surely had to be the plethora of old-school Karate masters who stayed behind in Okinawa, as a handful of daredevils crossed the waters to spread their beloved art of Karate to mainland Japan… and subsequently the rest of the world.

The result was what we see today: When you ask somebody to name a couple of styles of Karate, the answer will inevitably boil down to a) the style you practise yourself, along with either b) Shotokan, c) Shito-ryu, d) Goju-ryu or e) Wado-ryu. Why? Because those were the four big (excluding Shindo Jinen-ryu and Kushin-ryu, which never became as popular for several reasons) original styles being officially recognized in Japan by the Dai Nippon Butokukai (DNBK, the official Japanese governing body of martial arts) in the 1930’s.

Hence, when you ask somebody to name-drop a couple of famous Japanese Karate teachers, you will 9 times out of 10 get the names of the founders of the above styles. Funakoshi Gichin (Shotokan), Mabuni Kenwa (Shito-ryu), Chojun Miyagi (Goju-ryu) or Ohtsuka Hironori (Wado-ryu).

The interesting thing here, of course, is…

What about the guys left in Okinawa?

What about the numerous Karate masters who decided to simply remain in the birthplace of Karate, to further cultivate their art(s), instead of embarking on a grand mission to popularize Karate in an effort to aid Japan’s escalating WW2 war machine in spreading nationalistic propaganda and strengthening “imperial fighting spirit” [Jap. kokutai] and the unique feeling of “Japaneseness” [Jap. nihonjinron] (which was a major reason the Japanese government even considered popularizing this unsophisticated, unknown, fighting art from the backwater of Okinawa in the first place) throughout the nation? Huh?

History is rarely written by losers.

So let’s rewrite history.

Today I thought I would dive a little deeper into the history of some lesser-known, yet incredibly awesome, Karate masters from Okinawa. You know, those guys that just quietly did their own thang in Karate without becoming wildly popular in the process. Yabu Kentsu, Hanashiro Chomo, Kyoda Juhatsu, Anbun Tokuda, Shinpan Shiroma, Moden Yabiku, Chotoku Kyan… the list goes on. Those guys who stayed behind (okay, full disclosure: there were a couple of guys who stayed behind, whose Karate styles still became pretty popular in the world because of the many US military bases who later bought their Karate “services”, i.e. Seito Matsumura Shorin-ryu, Isshin-ryu, Uechi-ryu etc. Even today, some of these styles are more well-known in the USA than in Okinawa).

See, I keep getting these kinda e-mails a lot: “Jesse-san, why won’t you write about my master [insert super unknown Okinawan master’s name here]?”, or “Jesse-san, why won’t you write about my style [insert obscure Okinawan Karate style here]”.

Well, here’s why: Because, sadly, most people are not interested in weird Karate masters and original styles from Okinawa. Most people are not interested in archaic training methods, orthodox Karate teachings and/or stuff that’s not popular. We like popular stuff. We like stuff other people like. We like famous Japanese 3K (Kata, Kihon, Kumite) punch-kick styles from Tokyo. We are sheep.

But screw that.

You know that’s not how I roll.

To hell with my Google keyword ranking.

I want to take this opportunity to introduce to you one of the perhaps most underrated, super influential, incredibly old-school, historically significant Karate masters from Okinawa.

Sorry, that was a small lie.

He’s not actually a Karate master.

He was a master of “quan-fa”.

Or, as we like to call it today: “kung-fu”.

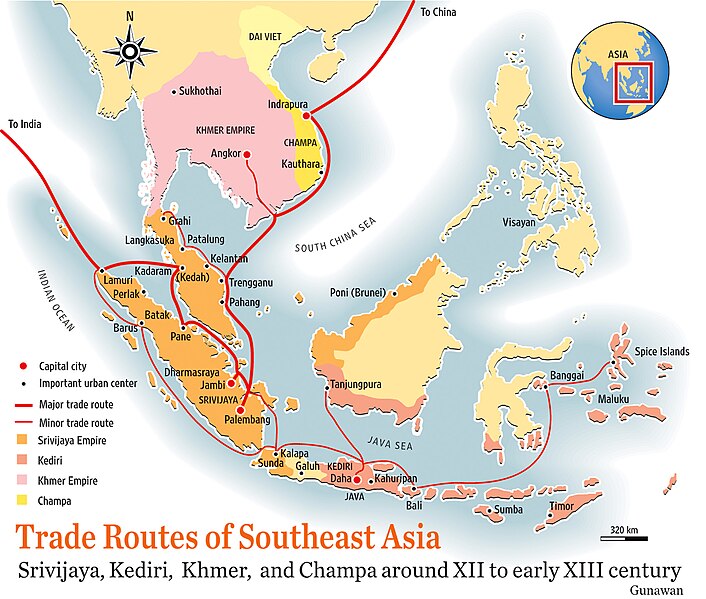

The thing is, original Karate was a mix of several fighting arts influences, stirred together in the pot of Okinawa.

A little Siamese boxing here, some Shuao Jiao wrestling there, some stick fighting from the Philippines, some xing/hsing from Taiwan, a touch of buki-gwa from Shanghai… add two essential ingredients known as Time and Open-Minded Culture, then multiply it with the number of foreign visits this small island of trade got during its heyday (know as the era of the Ryukyu Kingdom), you’ll pretty soon get the picture.

“Karate” (sic., the term didn’t exist at the time) was an eclectic mix of what worked and didn’t work in a physical confrontation.

With or without weapons…

So, naturally, some kind of order had to be created in this chaos.

Enter a Chinese gentleman known as Wu Xiangui.

An expert of ming he quan (“whooping crane boxing”).

Better known by the Japanese reading of his name: Go Kenki.

The star of this article.

Before we go any further though, you need to know that many Southern Chinese quan-fa masters influenced the local fighting arts community of Okinawa, ending up in this peaceful island through different means. Some came as officials on big Chinese tribute/trading ships (known as sappushi), some drifted ashore when they got shipwrecked, while others may have fled the 1900 Boxer Rebellion in China, searching refuge in the peaceful island of Okinawa.

Still, few of the Chinese quan-fa immigrants had the same practical impact as Go Kenki seems to have had on the local Karate community (okay, okay, let’s just briefly ignore the thirty-six Chinese families planted in Okinawa’s Kuninda district (Kume village), whose impact on the evolution of Karate I covered with hanshi Patrick McCarthy in The Matsuyama Theory (free e-book) which I seriously hope you’ve read and shared a couple of times already!).

How come?

Well, Go Kenki was one of the principal advisors to an incredible, underground, Illuminati-like, secret society of Karate masters in Okinawa, known as the Ryukyu Tode-jutsu Kenkyu-kai (lit. Ryukyu Chinese Hand Research Society).

A society created with the sole purpose of bringing order to chaos.

See, in 1918 a group of Okinawan Karate enthusiasts (including some famous people like Chomo Hanashiro, Chotoku Kyan, Nakasone Genwa, Chojun Miyagi, Kenwa Mabuni, Chojo Oshiro, Maeshiro Choryo, Kentsu Yabu, Juhatsu Kyoda, Moden Yabiku and Chibana Choshin) formed an exclusive research/knowledge exchange group for serious Karate study, since so many old grandmasters of the art had recentrly passed away (Anko Itosu and Kanryo Higaonna both died in 1915).

That’s right.

An open-minded, collaborative platform for Karate development.

(Curious: Where/why/how did we lose that idea in modern Karate?)

(Hey, don’t look at me, I’m trying!)

(Wonder what some living Karate legends think though? Look no further!)

This was the first time that practitioners of different “methods” (Shuri, Naha and Tomari-te) – later known as “styles” – met to train together in an informal setting to discuss and exchange information on the fighting arts. Each time they met, one senior would lead the training and all would benefit from their knowledge (this study group lasted until 1929 when, because of the popularity of Karate, most members all became too busy with their own students to train themselves!)

And here, during these formative years, is where most modern-day researchers believe Go Kenki played an integral part in shaping what we today call Karate.

Peep this:

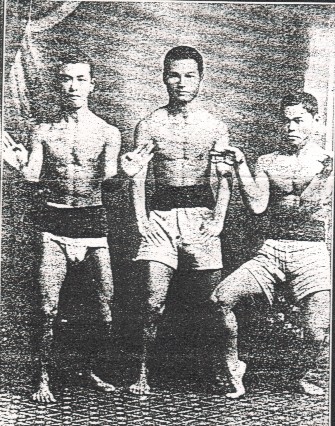

Go Kenki/Wu Xianghui (1886-1940)

Go Kenki was born January 20th, 1886, in a big family of three girls and four boys in Fuzhou City, Fujian Province. Historically, this was THE place to be if you wanted to become proficient in any form of nan-quan (southern fist boxing), including baihe-quan (white crane boxing) – of which Go Kenki was to later become an expert (more specifically, in the “whooping crane” form).

The reason Go Kenki initially started his quan-fa training was supposedly because of commercial interests (to serve and protect the blooming family business), since many of his relatives, including his uncle, were already schooled in the fighting arts.

Life in China became hard.

During the revolution in China, when most martial artists decided to escape to Taiwan (which is one of the reasons there’s so much old-school kung-fu in Taiwan these days), Go Kenki thought otherwise. He went to Okinawa instead (in 1912), where he eventually got married to a miss Yoshikawa, whose name he later took (which is why Go Kenki is also named Yoshikawa Kenki in some historical sources) and even had a daughter with.

At his arrival in Okinawa, Go Kenki started working as a secretary/desk slave in a tea shop. However, he quickly learned the trade and soon opened his own tea shop in Higashi, importing tea from China. The location of his new tea shop was no coincidence: Just a few short blocks away was Matsuyama Park, Kume Village (where he could hang with his Chinese peeps) and the top-secret historical area near Naminoue Jingu (Naminoue Shrine) where the Ryukyu Tode-jutsu Kenkyukai (the hidden underground Karate research society) had its headquarters.

Today, there’s mostly brothels and “love hotels” around this area.

(Uh, don’t ask me why I know this.)

(Just… dont.)

Anyways, umm… uh… *awkward*… the days of Go Kenki were spent working as a tea merchant, you know, importing/exporting herbs and spices, but in the afternoon he often closed his shop, the Eiko Koucha, in order to teach some martial arts to whomever might be interested instead. More often than not, the guys that were most interested in taking a part of Go Kenki’s advanced teachings happened to be a part of s “certain” society…

(By the way, legend has it that Go Kenki made so good money from his tea shop that all he required for teaching martial arts was one egg! Boiled, scrambled, fried or poached? The legend doesn’t tell. In any case, it’s fun to note that kung-fu masters get hungry for a late-night snack too. Apparently, he required his students to eat several raw eggs too. Perhaps salmonella just wasn’t as serious back then…)

Gradually, things started looking good.

Sure, Go Kenki didn’t have many students at first, but as soon as word-of-mouth marketing got going in da hood, he ended up being one of the principal figures of the Ryukyu Tode-jutsu Kenkyukai, regularely teaching a handful of selected local Karate masters (Mabuni, Miyagi, Kyoda, Matayoshi etc.) during his free time.

So what, exactly, did Go Kenki teach?

Well, we can’t know for sure, since he didn’t really record his experience (apart from the few photos floating around in this article). However, what we do know, from his extensive collaboration with people who DID write stuff down, is that he was the principal source of several white crane exercises handed down in Karate to this day, including kata like Happoren/Paipuren (the more advanced version of today’s Sanchin), modern versions on Hakucho, Haffa, Hakutsuru, Hakkaku (see Shito-ryu kata list) and Nipaipo (more correct name: Neipai). Researchers suggest he was the originator of moves like Tensho, kakie and tegumi exercises (which would come as no surprise, since these kind of close-quarter sticky-hand drills make up the meat and potatoes of white crane boxing applications) too, but we can’t know for sure.

What we do know, for sure, however, is that most contemporary schools of whooping crane boxing (just for your information, there’s many versions of white crane boxing; the main ones being whooping, singing, feeding and sleeping crane) teaches some of the following exercises (kata), which we can assume our dear Go Kenki taught too, in some form:

- San Zhan (3 Battles)

- Ba Bu Lien (8 Steps)

- Si Men (4 Gates)

- Ba Hua Lan (8 Flowerings)

- Er Shi Ba (28 Constellations)

- Shi Si Zi (14 Characters)

- Wu Shi Si Shou (54 Hands)

- San Shi Liu (36 Hands)

Of course, those of you who are linguistically inclined will be quick to notice the similarities in both name and meaning to several kata we practise today in Karate (San Zhan – Sanchin // Wu Shi Si Shou – Gojushiho // San Shi Liu – Sanseiru etc.).

In fact, many of these old kata still exist in the whooping crane system, although they are considerably more advanced than our modern Karate counterparts.

I mean, just for fun, contrast this Er Shi Ba (what we call Nipaipo or Naipai) video – the original being the top one, our modern Karate version the bottom one. You will, depending on your experience and abilities, undoubtedly see that the Karate version has omitted about 50% of the techniques, although the main directions (embusen) and unique technical characteristics of the form still remain somewhat intact.

And with those two vids I guess it’s time to wrap up this post on Go Kenki, the undercover kung-fu pioneer of Okinawan Karate.

In 1940, at the tender age of 55, Go Kenki passed away (blame it on the opium), forcing his family to move to Taiwan (where his daughter allegedly opened a white crane kung-fu school). What remains of that school today is beyond my knowledge, but what I do know is that if it hadn’t been for Go Kenki and his hands-on influence on the Ryukyu Tode-jutsu Kenkyukai and its incredible collection of open-minded Okinawan masters, we can be pretty sure that the version of Karate we practise today would look very, very, different.

Some styles, like Matayoshi-ryu, would perhaps not even exist.

As we already know though, history books are seldom written by losers.

Hopefully, we just made Go Kenki a winner then.

Fingers crossed.

24 Comments