There is a Chinese martial art that goes by the name of Wing Chun. Sometimes they spell it Wing Tsun too.

For those of you that have never heard about it, this was what Bruce Lee trained originally, before creating his own brainchild, Jeet Kune Do. Anyway, in Wing Chun they strike a lot, with their fists.

They really love striking. Like Karate.

But… there is one huge difference.

They always strike with the vertical fist.

Not like in Karate!

Why not? Is it better? More practical? Or is the horizontal Karate strike superior? Well, I have my theories as usual.

Let’s investigate a little.

First of all (for those with poor imagination), here is a picture of a vertical strike.

In Japanese we call this a Tate-ken. Vertical fist.

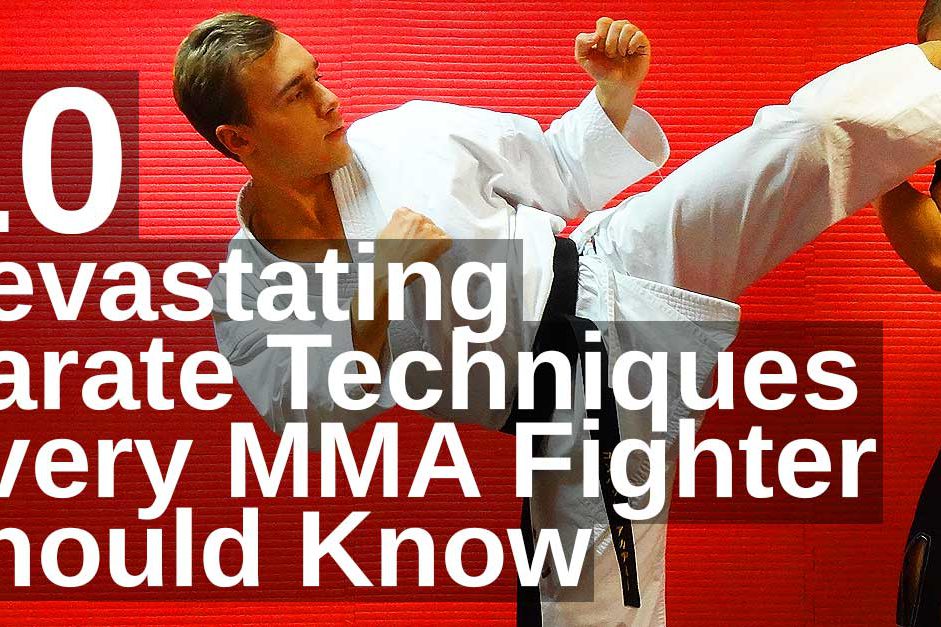

The opposite would be the “traditional” Karate punch, pictured below.

This is known as a Yoko-ken. Horizontal Fist.

Now, on one side we have some Chinese styles, like Wing Chun, and an Okinawan style, Isshin-ryu, that claims the vertical (Tate-ken) is better. On the other side we have Karate, Taekwondo, Boxing and some Kung-fu, that prefers the horizontal (Yoko-ken).

“My side” is that both are good, but the Yoko-ken is better, but only if you don’t misunderstand it.

And, sadly, I believe many do.

A comparison between Tate-ken and Yoko-ken is not that hard to do. Just try to do (correct) push-ups with both versions. A push-up is not that different from a punch.

You will immediately feel that the Tate-ken is indeed much more solid, and recruits the very important triceps and latissimus dorsi (your important punching-muscles) far better than your “normal” knuckle push-up does, while it effectively helps you from shrugging your shoulders at the same time, a common bad habit when doing push-ups.

The explanation for this is that the elbows are effectively kept tucked in when you do a Tate-ken push-up/strike. Looking at about 90% of the people doing Yoko-ken, the elbow points out.

And here lies the problem.

Because when the elbow points out… you loose energy. The energy splits. Some goes into your enemy, and some goes out to the side, through your elbow. Punching somebody like this is not optimal.

I believe this is because of a misunderstanding.

The misunderstanding is modernization of Karate. With its emphasis on long and large techniques (O-waza) the fixation of the elbow is effectively lost. But it doesn’t need to be, if you train corrctly from the beginning.

The Tate-ken does not have this same problem. At least not to the same degree. Using a Tate-ken, it is much easier to keep the elbow tucked in. The loss of elbow fixation usually occurs when you do that last turn, to make it a Yoko-ken.

What I’m trying to say is that the Yoko-ken can be better, but… only if you can do it with the body mechanics of a Tate-ken! And that’s where many fail.

This requires good muscular control.

Now somebody is going: “Why should you do that last twist anyway? Can’t you just leave it at a Tate-ken, and use that? Like in Wing Chun?”

No. Or, well, yes you can. But there is a valid reason for the last twist.

First of all, the last twist (known as the corkscrew) gives you more energy. However, the energy that this twist produces is minimal, so you can actually ignore this.

Secondly (and more importantly): Your forearm has two bones. A thick radial bone (radius) and a thinner bone (ulna). The corkscrew punch, Yoko-ken, makes your two forearm bones, radius and ulna, twist gradually around each other, making the whole structure of the forearm stronger, and able to withstand more force.

But be careful not to twist the hand too much. That would only make it worse. To find the proper balance is of utmost importance.

So, not only must you keep the elbow from flying out, you must also be careful not to “over-twist” the wrist! Add the proper details of hip work, legs, knees, shoulders, the back and some other stuff… and it really makes you wonder how hard a punch can be to learn!?

Maybe we should just stick to the old fashioned haymaker…

Lastly, even though Sport Karate makes it seem so, the Yoko-ken is not the only wrist formation used in Karate! It just happens to be the more popular one. As a matter of fact, the Tate-ken, and even the uppercut, are used in traditional Karate all the time. Examples can be found in the kata Chinte, Seienchin, Paiku, Seisan, Pinan, Gekisai, Heiku, Saifa, Suparinpei and many more.

No twist, half twist and full twist!

Yoko-ken might be the most popular version, but it is not the only version!

The tool depends on the target.

23 Comments