People keep e-mailing me on how to learn more about the history of Karate.

They’re lost.

And I totally understand them.

The vastness of historical Karate information online is baffling to say the least. To the uninitiated, finding valuable Karate info on the interwebz could be likened to finding the metaphorical needle in the haystack. You need to literally wade through tons of forums, message boards and questionable Wikipedia articles to find one ounce of new, verifiable, historical Karate knowledge that can take you further in your quest for becoming the best Karate-ka you can be.

It’s a jungle out there.

So of course people will e-mail me.

Because they know I like to keep it simple.

See, when it comes to understanding the history of Karate, I have a theory:

I believe it’s always in your best interest to just find a few good historical hotspots, milestones, events or people – and then simply use those as a starting point in your own “research”. By gradually identifying, learning about, understanding, and hopefully even connecting these historical high points then, you’ll eventually have a stronger grasp and clearer picture of the complete history of Karate than people who waste their time reading unreliable online articles, blogs, forums or books on the “Complete History of Karate from A to Z”.

Know what I mean?

So, with that being said, there’s a dude I think you need to learn about today. A guy who is as historically important to Karate as French fries are to hamburgers – if not even more.

His name?

Itosu.

Anko.

That’s right.

Itosu Anko sensei.

The “grandfather” of modern Karate – largely responsible for the fact that you and I are training Karate today (whether your sensei admits/knows it or not).

The man responsible for bringing the once obscure art of Karate out of its secretive darkness into the light of modernization.

Ever heard his name?

Of course you have. I mention his name several times throughout my articles. And so do many other people, he’s a Karate legend. But still… you don’t really know that much about him… do you?

Here’s the only picture (discovered quite recently) of Itosu sensei:

So who is this man, Itosu Anko, (some Japanese people also incorrectly pronounce his name Yasutsune) really then?

Well, that’s what I thought we could try to figure out today, by revisiting and analyzing his epic historical essay on the “Ten Lessons of Karate”, an important document Itosu sensei wrote in 1908 which ended up providing the very infrastructure upon which the modern tradition of Karate unfolded.

Sounds cool?

That’s what I thought.

But first things first:

You see, Itosu Anko, who was born in 1831 as an allegedly shy and introverted child, was active in the Okinawan Karate community during a very special time: A time when the Japanese army seriously considered officially importing Karate to mainland Japan (because they were so impressed by the physical conditioning of several Okinawan conscripts during their medical examinations in 1891), but ultimately ended up losing interest in it because of its outdated training methods, poor organization, lack of standardization and the great length of time it took to gain proficiency in the art. In other words, old-school Karate training could not adequately serve the needs of the six- to eight-week boot camp training which the Japanese military demanded.

However, that was not until a unique campaign surfaced, spearheaded by none other than a certain Itosu Anko sensei, with the aim of modernizing Karate’s practice and purpose to spread its popularity.

A bold move, which would forever put this locally respected Okinawan Karate teacher in the annals of Karate’s history.

Strongly believing in the greater value of Karate for youth development, in 1901 Itosu sensei had begun teaching old-school Karate at the Shuri Jinjo Elementary School, and then in 1905 at the First Junior Prefectural High School and at the Okinawa’s Teachers College.

In other words, he was the first sensei trying to actively open up the previously secretive art of Karate to larger groups, and in the process ended up discovering that the old ways of teaching did not always appeal to the youth. So, in turn, he set out to improve Karate; for instance by developing the Pinan/Heian kata (to coordinate the previously sporadic introduction of Karate techniques for beginners), as well as reorganizing, simplifying and dividing many of the older kata (like Naihanchin, Kusanku, Gojushiho, Passai etc.) of Okinawan Karate.

In other words, by linking the past to the present, Itosu’s crusade to modernize Karate resulted in fundamentally altering its practise.

For good and bad.

With master Itosu removing much of what was then considered too “dangerous” or “inappropriate” for schoolchildren to learn (hey, would you want your kids to learn groin kicks, eye gouges or headbutts in school?), the emphasis of Karate radically shifted; from a sophisticated art of self-defense to a new model of physical fitness – heavily emphasizing things like the value of group kata practise (but at the same time neglecting its original purpose of bunkai) and kihon techniques.

In this way, ignoring the spiritual foundation upon which Karate once rested, and no longer advocating its original self-protective principles (to immobilize or maim an opponent), the old discipline of Karate became obscured and a new tradition evolved. Things like kata – once believed to hold the deeper essence of Karate – virtually became reduced to exercises for health, fitness and recreation.

This radical transition period, headed by Itosu sensei, ended up representing the ultimate termination of a previously secret self-defense art and the birth of a modern Karate phenomenon.

And what a ride it was.

As history then tells us, the movement was ultimately culminated in Karate becoming a part of the official physical education curriculum of Okinawa’s school system at the turn of the century, eventually making its way to mainland Japan (giving rise to school/university clubs, tournaments, mass teaching methods, rankings/belts, instructor courses etc.) and later the rest of the world.

But… how did he do it?

I mean, how did one man set in motion this huge machine of global Karate development?

(Of course there were other influential people taking part in this process too, but Itosu sensei was the principal progenitor.)

Well, if you ask me, one of the main reasons for the success of Itosu’s campaign for spreading Karate was his 1908 address to the Ministry or War and Ministry of Education, an essay nowadays referred to as the “Ten Lessons of Itosu”, where Karate’s true aims and objectives are succinctly laid out by master Itosu himself in order to convince the leaders of Japan to introduce Karate to the educational system.

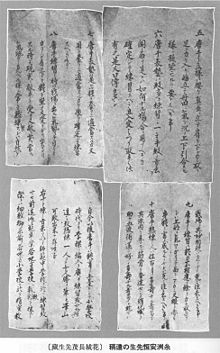

This letter, which fortunately enough survived the WWII bombings of Okinawa, still exists to this day – and has given a lot of researchers epiphanies when trying to better grasp the totality of Itosu’s masterplan through analyzing his preserved manuscript on the essence of Karate.

And if I know you right, you’re dying to read it by now (right?)!

So, to help you better understand the history of what you practise today (and why!); today I have the exclusive permission and pleasure of re-publishing an original translation of Itosu Anko’s essay in question, skillfully translated by Patrick McCarthy sensei, the Western world’s foremost researcher and author on Karate’s history and culture.

Because, like I mentioned in the beginning, let’s face it: Although it would be cool for you to read tons of Karate history books, I believe it is way more practical for you to just get a grip on a few noteworthy historical points in the timeline of Karate (my job is to expose you to that) – with this document being one such milestone.

Also, and I hope you don’t mind, I took the liberty of chopping up the essay to sprinkle it with my own commentary.

Hopefully it will prove a valuable addition to the original translation.

(If not, sue me.)

Now, enjoy:

“Ten Lessons of Karate”

Intro:

“Karate did not descend from Buddhism or Confucianism. In the olden days two schools of Karate, namely the Shorin and Shorei style, were introduced from China. Both support sound principles, and it is vital that they be preserved and not altered. Therefore, I will now mention here what one must know about Karate.

Right off the bat, Itosu makes it very clear that Karate has no religious foundation (although some present-day “masters” undeniably seek to give Karate pseudo-Buddhism/Confucianism undertones). It is a martial art, period. He then goes on to state that two distinct Chinese styles of martial arts influenced Karate historically (which researchers suggest could be the ‘northern/southern’ kung-fu styles, Shuri-te/Naha-te, or the so called ‘internal/external’ (hard/soft) kung-fu), but that they both rely on the same basic principles, which he then outlines in his ten following precepts.

1. Karate does not only endeavor to discipline one’s physique; if and when necessity arises whereby one has to fight, Karate provides the fortitude in which to risk one’s own life in support of that effort. Karate is not meant to be employed against an adversary, but rather as a means to avoid the use of one’s hands and feet in the event of a potentially dangerous encounter.

As his first point, Itosu basically states that although Karate will get you in great shape and make you physically stronger, it will also give you the self-confidence and mental strength you need in order to successfully avoid a possible encounter – and if that doesn’t work it will give you the courage to even sacrifice your own health for the greater cause.

In essence, Itosu defines Karate as a defensive martial art used as last resort.

2. Karate’s primary purpose is to strengthen the human muscles, thus making the physique as strong as iron and as hard as stone. One may then use the hands and feet as weapons – such as the spear and halberd. In doing so, Karate training cultivates bravery and valor in children and should, therefore, be encouraged within our elementary schools. Do not forget what the Duke of Wellington said after having defeated Emperor Napoleon: “Today’s victory was first achieved from the discipline attained within the playgrounds of our elementary schools.”

Now, Itosu seems to get a bit more political with his message (which shouldn’t come as a surprise, since the original purpose of writing this text was to convince the authorities of Japan to make Karate mandatory for schoolchildren, after all).

He boldly states that the primary purpose of Karate is to strengthen the various muscles, and make your hands and feet sharp as spears; implying that if all schoolchildren of the nation were to practise Karate, the country would even eventually be so powerful that it could have kicked Napoleon’s ass! In this last statement, the highly educated Itosu reveals his knowledge of Western culture and military history by attributing a quote to the Duke of Wellington, further improving his case.

3. Karate cannot be adequately learned in a short time. Like a torpid bull, regardless of how slowly it moves, it will eventually cover 1,000 miles; and so it is for the one who resolves to study diligently two or three hours each day. After three or four years of unremitting effort, one’s body will undergo a great transformation, thus revealing Karate’s very essence.

Not wanting Karate to look like a ‘get-rich-quick’ scheme, Itosu now proceeds to tell us that Karate is a serious endeavor and will take time to adequately learn. Karate is not a fad, it requires great resolve and diligence. But when it has been deeply studied, for a few hours each day over a few years, it will have radically transformed you. In other words, it might take time – but it will totally be worth it.

4. One of the most important issues within Karate is the training of the hands and feet. Therefore, one must always use the makiwara [traditional Okinawan punching board] in order to develop them thoroughly. To do this effectively; lower your shoulders, open your lungs, and focus your energy. Grip the ground firmly in order to root your posture and sink your ki – commonly referred to as one’s life force or intrinsic force – into your tanden (spot just below the navel). Following this procedure, perform 100-200 tsuki (thrusts) each day with each hand.

Itosu now slowly starts sailing more and more into the combative aspects of the art. In this fourth precept he goes into detail on how to properly prepare for, and use, the makiwara. Since the makiwara was the #1 impact training tool at the time, this would translate in today’s terms to using a punching bag, focus pads, kick shields or similar. Although many Karate-ka these days would consider these implements pretty “non-traditional” for Karate, using gear like these clearly seem to be pretty much in line with what Itosu sensei was encouraging: Heavy impact training used in an intelligent way for developing your technique.

And still we’re punching in the air…

5. One must maintain an upright position withing Karate’s training postures. The back should be straight, loins pointing upward with the shoulders pulling downward, and a springiness should be maintained in the legs. Relax, and bring together the upper and lower parts of your body with the ki force focused in your tanden.

Here Itosu goes more into the postures and stances of Karate, if only on a very basic (yet highly important!) level. As a sidenote, it’s pretty surprising to me that so many people have such a hard time with these basic points of Karate’s combative posture, but I guess it’s just a matter of practise.

(Why the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of War in Japan would be interested to read these points are not really clear to me, but I have a feeling Itosu is slowly losing track of his political agenda and is now undoubtedly revealing some of of his true Karate Nerd™ nature. I recognize the situation!)

6. Handed down by word of mouth, Karate comprises a myriad of techniques and corresponding meanings. Resolve to independently explore the context of these techniques, observing the principles of torite (grappling/joint locks) with the corresponding theory of usage – and the practical applications will be more easily understood.

Stabbing right at the heart of many modern-day “kata bunkai experts”, Itosu here clearly states that there never were any real written records on the meaning of Karate’s numerous movements – so you will therefore need to independently explore the various techniques of Karate yourself; including grappling, joint locks, takedowns and escapes (collectively referred to as torite in old-school Karate) in order to truly understand the various possible applications of Karate’s techniques in general, and kata in particular.

As he also states, the context of these techniques is highly important too: When studying kata – which is, after all, a record of the original Karate Itosu is trying to describe here – we need to ensure that we understand that kata were created to record methods for civilian self-defense, and not mano-a-mano fighting (à la MMA or dojo sparring).

It is when people view kata from an eye-to-eye/fistfight perspective that they misunderstand the nature of its applications (bunkai) and subsequently come to incorrect conclusions about how effective kata applications should look. Things like fancy footwork, different guards and openings, cool feints, various tactics, combinations and rhythms are great to practise for a consensual fight but are irrelevant for civilian self-defense; which is why such methods never appear in kata.

Sure, you can force a square peg into a round hole, but it won’t look right.

Itosu tries to tell us this.

7. In Karate training, one must determine whether a specific application is suitable for defense or for cultivating the body.

Now, at this point, something tells me Itosu had the same problem back in his days as I have now: People keep asking if this or that technique would work in the notorious ‘street’. However, instead of slapping his students silly, Itosu simply writes an acknowledgement in this precept that that yes, there are in fact some moves in Karate which are not suited for self-defense (but rather designed for “cultivating the body”) and a distinction must be made between these, lest one wishes to end up with a big hospital bill. Couldn’t have said it better myself.

This holds especially true for the more modern types of Karate, where unnaturally deep stances, unrealistic 1-2-3 step sparring and flashy kicks seem to be more predominant. Your mileage may vary.

8. Intensity is an important issue for Karate training. To visualize that one is actually engaged upon the battlefield during training does much to enhance progression. Therefore, the eyes should dispatch fierceness while the shoulders must be kept low; contract the body whenever lowering the shoulders, and contract the body when blocking a strike or delivering a blow. Training in this spirit prepares one for actual combat.

Echoing the words of legendary samurai warrior Musashi, here Itosu goes even further into the combative aspect of Karate; advising us to keep the same mindset in the dojo as in the pub. In other words, you are what you eat. Practise what you preach. The more you sweat in the dojo, the less you will bleed in the unforgiving street.

By regulting your intensity in practise (trying to match it with your expectations of reality) you will be better prepared when/if the time comes for you to actually use your Karate in “actual combat” (jissen). For most of us that time is never, but hopefully the mindset will carry over to other aspects of your life.

9. The amount of training must be in proportion to one’s reservoir of strength and condition. Excessive practise is harmful to one’s body, and can be recognized when the face and eyes become red.

Now, with the previous precept just being written (on the intensity of practise), Itosu suddenly seems to remember that not everybody need to kick themselves in the ass as hard. Karate is a way of life, and as such should promote the health of its practitioners. Adapt the intensity and volume of training to your own capabilities (making sure not to get stuck in any comfort zone though!) in order to have a long and prosperous Karate career.

10. Karate practitioners usually enjoy a long and healthy life thanks to the benefits of unremitting training. Practice strengthens muscle and bone, improves the digestive organs and regulates blood circulation. Therefore, if the study of Karate were introduced into our curricula from elementary school, and practised extensively, we could more easily produce men of immeasurable defense capabilities.

With these teachings in mind, it is my conviction that if the students at the Okinawa’s Teachers College practise Karate they could, after graduation, introduce Karate at the local levels; namely in the elementary schools. In this way, Karate could be disseminated throughout the entire nation and not only benefit people in general but also serve as an enormous asset to our military forces.

Itosu Anko,

October 1908 (Meiji 41, Year of the Monkey).”

Finally, ending his essay by going back on track with his original mission (getting Karate accepted for school), Itosu hints at the possible benefits for the country as whole – both in the military, educational and health sectors – if Karate were to be accepted by the authorities.

And, as you and I are living proof of, he succeeded.

Although the subsequent popularization of Karate produced numerous “offsprings” of various quality and quantity (and new ones pop up every day) the historical significance of Itosu’s original movement, as embodied in his above essay, remains vital and shouldn’t be forgotten.

At least that’s what I think.

And yes, the history of Karate is messy. But those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Therefore, I encourage you to share this article with your peers.

I just opened the door.

You decide if you’re going to enter.

36 Comments