Does success always equal fame?

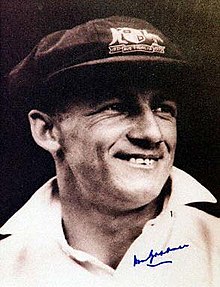

If your answer is yes, how come you have never heard of Donald Bradman?

Probably because sir Donald Bradman (1908-2001) was an Australian cricket player. (You know, cricket; that ol’ English bat-and-ball game which at first view looks similar to baseball). Now, although cricket isn’t the world’s most well-known sport, it is safe to say that Donald Bradman – a virtual legend in the cricket world – was actually the best athlete who ever lived.

That’s right.

The best athlete who ever lived.

All sports combined.

(And most people have never heard his name!)

By any statistical measure, sir Donald Bradman (or “The Don”, as he was sometimes called) was comparatively the very best at what he did. He was far better at cricket than, for example, Michael Jordan was at basketball, Wayne Gretzky at ice hockey or Jack Nicklaus was at golf.

It’s very difficult to be as good as Donald Bradman.

In fact, it’s pretty much impossible.

Bradman’s batting average of 99.94 has been claimed to be statistically the greatest achievement in any major sport (because his batting average is 4.4 standard deviations above the average of other cricket players), with the great Pelé coming in second on that list (at 3.7 standard deviations above the mean for goals per game) in soccer.

In other words, Donald “The Don” Bradman is, statistically, the greatest athlete ever to play ANY sport.

As journalist John Kieran wrote in the New York Times (in 1932) – “According to evidence submitted by interested parties, Donald Bradman makes so many runs that the scorekeepers no longer go into the details choosing merely to ring a bell as he passes each century. He simply keeps hitting and running until some sensible person in the stands suggest a cup of tea.”

And the cool thing is, The Don dominated his peers not because of greater height, strength or size (like a lot of modern famous athletes do, especially in combat sports) but purely with his amazing skills.

Apparently, Walt Disney even named Donald Duck after him!

Apparently, Walt Disney even named Donald Duck after him!

(Seriously… this guy was off the hook!)

But here I go, digressing again.

You see, what I really wanted to talk about today wasn’t cricket, sports or even records.

I’m here to talk Karate.

I just used cricket, and the remarkable example of Don Bradman, to highlight the fact that even though you might statistically be the best athlete to ever live, you don’t necessarily have to be as famous as comparably “less talented” athletes like Lance Armstrong, Mike Tyson, Tiger Woods, David Beckham and others.

Success doesn’t always equal fame.

And the same goes for Karate, of course.

Question:

Have you ever heard of Konishi Yasuhiro?

I bet you haven’t.

(If you have: Congratulations! You have now earned official Karate Nerd™ bragging rights for a full 1,5 minutes in your next Karate class!)

Konishi Yasuhiro (1893-1983), perhaps the most successful leading pioneer of Karate from the Japanese mainland, was by far one of the most important figures in contemporary Karate history.

No joke.

It is safe to say this: Not only was he one of the driving forces behind getting Karate accepted in Japan as a “new” martial art from rural Okinawa, but he was also one of the main sponsors for Karate legends like Mabuni Kenwa (founder of Shito-ryu), Miyagi Chojun (founder of Goju-ryu), Funakoshi Gichin (founder of Shotokan), Motobu Choki (notorious Karate street-fighting expert and founder of Motobu-ryu), Ohtsuka Hironori (founder of Wado-ryu) and Taira Shinken (the grandfather of Ryukyu Kobudo) – even hosting these masters in his house, arranging for meetings/training camps, paying for trips and food – among other things.

Konishi Yasuhiro – one of the least known yet most influential Karate masters of all time – was truly an original Karate Nerd™ during his days.

Yet he had to pay a heavy price.

As Konishi’s own son (Takehiro) once told me personally, Konishi was severely criticised by jealous students of the many masters he helped, sometimes even being called a “geisha” behind his back, for traveling between the various masters in order to learn as much as possible about this fascinating art of Okinawan Karate that was just being introduced to Japan.

Because, the thing is, Konishi wasn’t originally a Karate-ka.

Born in 1893 in Takamatsu, Kagawa, Konishi began training in Muso-ryu ju-jutsu at the age of six, which was followed by kendo (the Japanese art of fencing with bamboo swords) when he was 13 and later, Takenouchi-ryu ju-jutsu (a style known for its strong atemi-waza, i.e. kicks and punches).

In other words, Konishi sensei’s background was strict samurai style, mastering both armed and unarmed combat.

In 1915, Konishi began studying at Keio University, one of the most famous universities in Tokyo. While average tenure at university is four years, Konishi remained at Keio University for eight years (!) because of his love for kendo and ju-jutsu, as he was Keio University’s kendo team captain – and continued coaching the university’s kendo club even after his graduation.

So far nothing special.

Until Karate came knocking on the door.

Literally.

In September 1924, Ohtsuka Hironori and Funakoshi Gichin came to the kendo training hall at Keio University. Stepping inside after the kendo session was over, they approached the teacher, Konishi sensei, with a letter of introduction from professor Sadahiro Kasuya of Keio University. Mr. Funakoshi, who wasn’t yet as famous as he later would become, asked Konishi if it would be possible to use the training hall to teach something called “Ryukyu Kempo Toudi-jutsu” (the old formal name of Okinawan Karate).

Konishi sensei, a hardcore martial arts lover, was naturally intrigued.

Now, at this point there is something you need to know: During this era, it was unheard of for one martial arts school to allow a martial arts teacher from another system to teach in their dojo. Really. Such a request would be considered a “challenge” to the dojo. Konishi sensei, however, who was something of a visionary in the sense that he saw value in cross-training, immediately remembered a kata demonstrated during his university days by a friend from Okinawa named Aragaki, and he quickly agreed to Funakoshi sensei’s request, perhaps sensing that this could be a golden opportunity for himself to learn more.

Well, one thing led to another, and before you knew it Konishi Yasuhiro had not only helped Funakoshi establish the first university karate club in Japan, but he had made friends with a plethora of other Karate masters from Okinawa who were visiting mainland Japan to spread their beloved art of Karate.

And Konishi was more than happy to help them, eagerly learning as much as he could from them in the process.

In his quest for helping to popularize Karate, Konishi sacrificed a lot of personal time and money (luckily, his wife wholeheartedly supported his quest, since his work as a businessman helped cover the extra expenses). For instance, Konishi had Mabuni sensei reside freely at his house for almost a year, organized the ‘Choki Motobu Support Society’ for master Motobu (who Konishi considered a brilliant expert) and most notably paved the way for Karate to become formally accepted in 1935 by the Japanese Governing Body of Martial Arts (the Dai Nippon Butoku-Kai) as an official martial art.

That’s right.

He wasn’t gonna let this awesome “Karate” thingy be put on the back burner.

And funnily enough, the first Karate teaching license ever issued in Japan was actually a “kyoshi” title to Konishi sensei himself (a fact which infuriated students of the various Okinawan/Japanese masters from whom Konishi had been learning for so long).

Nonetheless, most of these masters were naturally deeply thankful of Konishi’s support, like Miyagi Chojun (Goju-ryu) for instance, who presented Konishi with an original manuscript, (“An Outline of Karate-Do”, March 23, 1934) which to date remains one of the most sacred texts on Karate’s true history, aims and original values. (I promise to post the translation one day.)

As Karate was now spreading far and wide throughout Japan, largely through the unwavering efforts of Konishi sensei, he ultimately decided to pool together the knowledge of his great teachers and name his own style Shindo Jinen-ryu (lit. “godly, natural style, complete empty-handed way”).

Okay, hold up a sec.

I can sense what you’re thinking:

“Whoah… Jesse-san, did this Konishi dude get hubris or what?”

Yeah.

Well, not really.

First of all, it is sort of a tradition in many Japanese martial arts to name your style ‘godly’, ‘divine’ or ‘complete’. Many traditional Japanese budo schools have those attributes, so that’s nothing new.

Secondly, sensei Konishi believed that if you walk a morally correct path in this life, you are naturally always following the ‘divine’ way. In other words, if you train in Karate in a ‘natural way’ and master your body, you will expand your knowledge and experience, and eventually establish a solid foundation for naturally living a morally correct and awesome life.

And so Konishi’s style, on the recommendation of the founder of the aikido (Morihei Ueshiba, with whom he actually co-created the kata called Seiryu) came to be Shindo Jinen Ryu Karate-jutsu.

(Which is the basis for the Karate style that I actually teach. But hey, you already knew that, since you’ve read my About page fifty times at least, right?!)

All right, all right, all right…

All right.

This article is about to end.

My goal today was to inform you that, just like Donald Bradman (the cricket player), Konishi Yasuhiro sensei was one of the most successful figures in his field. It is almost an understatement to say that Karate would surely not be what is is today if it wasn’t for Konishi sensei and his deep passion for Karate (along with some minor political maneuvers, obviously).

Yet he never became as famous as the masters he helped get to the top!

Why?

Well, if I remember correctly, when I met Konishi’s son (for the record: I’ve only met him once, and although cancer had made his speech impaired due to his swollen face, his mind seemed clear), he told me that the reason his father’s style of Karate didn’t become as popular as the other four major Japanese Karate styles (Shito, Wado, Goju and Shotokan) was because of two main reasons:

- Konishi sensei didn’t like competing (which made it less appealing to young people, compared to other styles)

- Konishi didn’t write a book (because he wanted to keep control of who was being taught what)

In contrast, many other styles/masters of Karate openly encouraged competing (Mabuni and Taira even developed the first protective gear for Karate) and wrote popular books and technical manuals on Karate.

But, as we know, success isn’t really measured by fame.

By the time Konishi sensei passed away, he was deeply impressed by the fact that Karate was so widely recognized by the general public – the fact that he could have obtained a lot of fame was of no concern. At his traditional Japanese ‘beiju’ celebration (commemorating his 88 years of age), Konishi held one of his last speeches:

“The things a man can do throughout one’s short life might be very little, but anyone can achieve at least one great thing if one tries one’s best, without expecting too much. […] Success might be the best, but even if one fails to attain what one expected, the fact that one tried one’s best should be recognized and that has meaning to one’s life.”

In 1983, Konishi Yasuhiro passed away, entrusting his son Takeshiro (who later changed his name to Yasuhiro in memory of his father) with future affairs.

Konishi sensei was a strong believer in the fact that there ultimately is no significant difference between the various martial arts; whether it’s judo, kendo, ju-jutsu or karate. They are all fundamentally one and the same in the end.

Most of us have two arms, two legs and one head.

There are only so many ways they bend.

At the end of the day, I believe Konishi Yasuhiro’s sophisticated-yet-down-to-earth philosophy of Karate was perhaps best expressed in the following traditional Japanese-style poem which he once wrote:

Karate is

Not to hit someone

Neither to be defeated

But to avoid trouble

That’s it for today guys.

Hope you learned something new.

41 Comments