When, and how, did Chinese Quan-fa (Gong-fu/Kung-fu) arrive in Okinawa?

This is a question that has bugged many researchers for years, and today many theories exist.

One major problem is the lack of written material dating from that time. Since America tried to bomb Okinawa back to the stoneage, pretty much everything was destroyed. However, one interesting piece was saved, and that is something called “The Oshima Incident”:

In 1762, an Okinawan tribute ship (on its way to to Satsuma, Japan) was blown off course during a nasty typhoon and drifted to Oshima beach on Shikoku Island.

On this island lived a confucian scholar, named Tobe Ryoen, who had a passion for writing. Upon hearing that a ship had stranded on the beach, he enthusiasticly grabbed his brush and rice-paper, and recorded everything in a chronicle entitled “Oshima Hikki”, which translates to “The Oshima Incident”.

Basically, he wrote down everything about the ship, its crew, and so on.

In a dialogue with an Okinawan officer from the boat, (named Shiohira), who was responsible for the kingdom’s rice supply, there appears the name of a Chinese called “Kusankun” known among karate historians today as Kusanku/Kushanku or Koshankun. In the conversation, he is described as an expert in “kempo” (lit. fist-method), and it is believed that this man, Kusankun, travelled to the Ryukyu Kingdom (Okinawa etc) with a few desciples, in 1756.

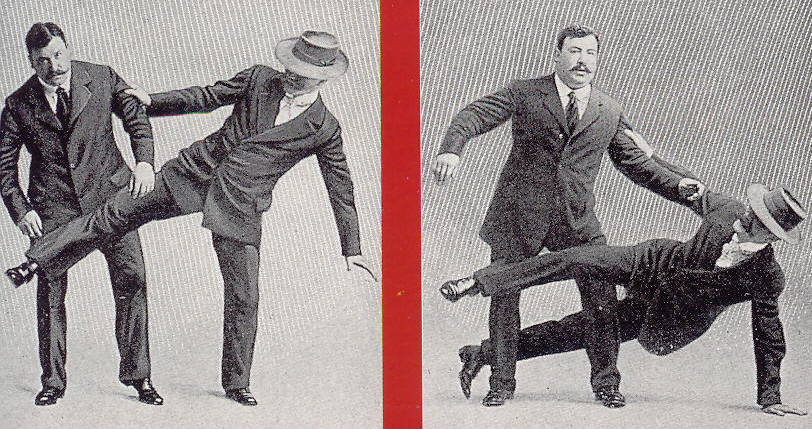

Apparently, the officer (Shiohira) and Ryoen (the confucian scholar) talk about martial arts, and the name Kusankun is mentioned when Shiohira tells Ryoen a story. Recounting how impressed he was witnessing a person of smaller stature overcome a larger person, Shiohira described what he remembered:

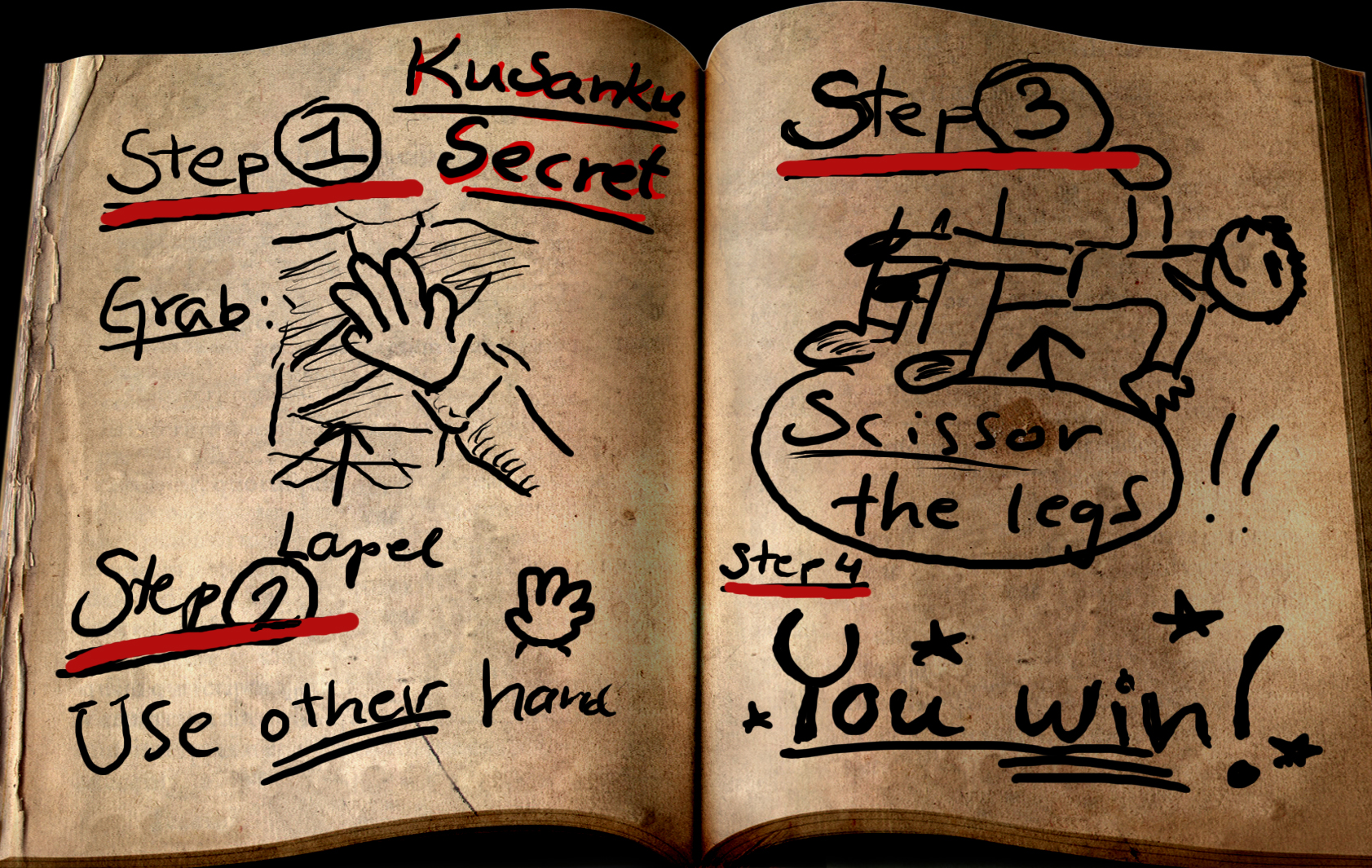

“With one hand placed upon his lapel and the other applying his “kumiai-jutsu”, he

overcame the attacker by scissoring his legs.”

When describing Kusankun’s leg technique, Shiohira used the term “sasoku,” which roughly describes the scissors action of a crab’s claw¹.

Even though Shiohira’s description of Kusankun is quite short, it remains the most reliable early written proof regarding the Chinese influence on the “civil fighting traditions” in Okinawa. However, the two dates mentioned (1756 & 1762) have been checked by researchers, and no official records of any Kusankun/Koshankun/Kushanku has been found in neither Beijing nor Fuzhou, which would suggest that he was not sent or invited (at least not officially).

So what is the conclusion?

Let’s take it from the beginning:

A Chinese martial arts expert, named Kusankun, travels to the Ryukyu Kingdom, with a few disciples, in 1756. On his way there, he meets some important people (among them Shiohira) to whom he demonstrates his martial arts skills.

He most certainly shows something along the lines of grappling/joint-locks (hence the term kumiai-jutsu), placing one hand on the opponents lapel, and the other hand applying some sort of grappling move. He then proceeds with a takedown, using a scissoring movement with his legs.

Most likely something like this:

One of the onlookers – a man responsible for the kingdom’s rice supply – whose name is Shiohira, is very impressed by how a small man like Kusankun can effectively subdue a bigger man.

In fact, Shiohira is so impressed that six years later, when he shipwrecks on Shikkoku Island and is interviewed by a confucian scholar (Tobe Ryoen), he mentions this remarkable demonstration he once witnessed by “a man named Kusankun“. Isn’t that remarkable.

“Yeah, yeah, what has this got to do with anything?!” you’re probably thinking.

Wait, I’m soon there because there is another very interesting piece in this puzzle:

We actually have some kata(s) today called Kusanku (Dai & Sho, Chatan Yara). You might even know them.

What a coincidence huh!? It’s the same name!

So there was a Chinese master in 1756 who went by the name of Kusankun, and a kata that we practise today is called Kusanku (or Kushanku/Kosokun/Kanku/Kwanku).

Wohoo, success!

Let’s briefly look at the kata then:

Kusanku Sho and Kusanku Dai are practised all over the world. They come from the Itosu-lineage. Itosu Anko was a man who learned kata, and changed them for the school system. The original kata was called “Chatan Yara Kushanku” This kata can still be seen in Okinawa (not to be confused with the mutated tournament version). Itosu is believed to have learned the original Kusanku kata (Chatan Yara Kushanku) from Mr. Yara, who lived in Chatan village, and made two simplified versions, named Sho & Dai (small & big).

So what does all of this mean? I am a bit confused myself. All of these names and dates…

Conclusions based on the above text:

1. The original Kusanku kata (Chatan Yara Kushanku) may have a “grappling-technique-in-combination-with-leg scissoring” application. What, or where, this application is to be found is up to you!

2. Chatan Yara Kushanku is perhaps the oldest form (kata) that is still preserved today. If it wasn’t altered along the way.

3. Thank heaven for confucian scholars who write down seemingly boring and trivial everyday-stuff that becomes highly interesting for Karate Nerds 250 years later.

4,5,6,7,8,9… Think for yourself (it’s more fun that way)!

The story of Oshima Hikki and Mr. Kusankun still remains the subject of intense curiosity!

______________

¹This move was used in oldern Judo as well (kami-basami=crab scissors), but has now been banned because of numerous busted kneecaps.

12 Comments