Continued from part 2.

Mabuni’s teachings and research

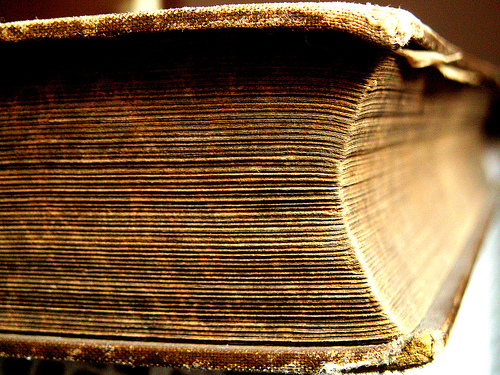

Mabuni wrote down his beliefs and philosophies about Karate in four significant books: ‘Karate-jutsu’ (The techniques of the Empty Hand, ca. 1933), ’Kobô Jizai Goshinjutsu Karate Kenpô’ (The Free Fist Method of the Empty Hand as an Art of Self-defense, 1934), ’Seipai no Kenkyû’ (Research on Seipai, 1934) and together with Nakasone Genwa (1895-1978) ‘Karate-Dô Nyûmon’ (Introduction to the Way of the Empty Hand, 1st ed. 1935, 2nd ed. 1938).

Mabuni also wrote for Nakasone Genwa’s ’Karate Kenkyû’ (Research on the Empty Hand, 1934) the two chapters ’Kata wa Tadashiku Renshû Seyo’ (Practice Kata Correctly) and ’Kumite no Kenkyû’ (Research on Kumite), as well as for Nakasone’s mammoth-work ’Karate-Dô Taikan’ (Overview on the Way of the Empty Hand, 1938) a chapter about the ’Aragaki Sôchin’-form, and various newspaper articles.

Mabuni also planned a book about the ’Sôchin’ and ’Kururunfa’-forms (‘Gojû-Ryû Karate-Dô Kenpô, Sôchin and Kururunfa’). To Mabuni these Kata have been of higher interest, as they contain special grappling-techniques, uncommon throws and reverse head-butts to the solar plexus, among much more. Although the book was advertised in other publications, it was never written.

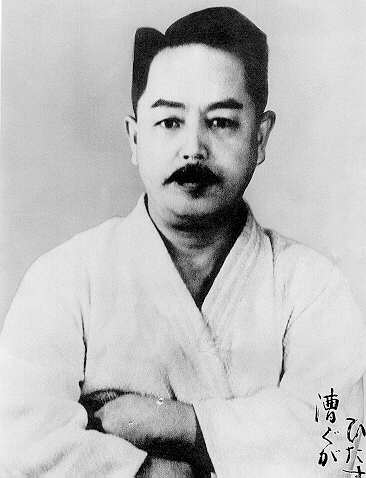

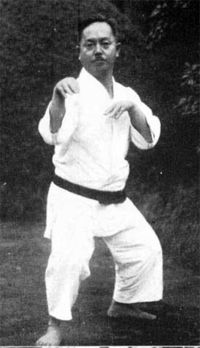

None the less, Mabuni is also, in view of his publication’s both quality and quantity, one of his era’s leaders. All the pictures in his publications demonstrate his thereby outstanding technical level. His techniques appear quite mature and acutely precise in their execution.

Mabuni must have been almost obsessed by the ’Art of the Empty Hand’ and must have had absorbed all available information like a sponge. “The only thing he was edacious for was Budô” reports his son Kenei. He knew both elements of Shuri- and Naha-Te like no other, and combined them in his unique synthesis, Shitô-Ryû. The influence of the Aragaki-school and Go Kenki’s Baihe Quan can also still be found in the style today.

Mabuni’s versatility is clearly evident by his use of an impressive 53 Kata. In his time, this high amount of style-specific Kata was unparalleled. It is most likely that Mabuni knew exactly about the uniqueness of his knowledge and that he made his selection especially to preserve a wide spectrum of Kata for the upcoming generations. Maybe Mabuni also wanted to show the complexity and diversity of Ryûkyû’s cultural heritage, and prevent further stereotyping of a ”farmer’s fighting style“.

In view of Shitô-Ryû’s amount of Kata, one has to keep in mind that Mabuni himself never regarded a deep understanding of all these Kata as really important for the mastery of his style. Like Funakoshi Gichin, Mabuni was also an advocate of the ’Hito Kata San Nen’-maxim. Three years constant practise of one Kata was during those days the amount many masters regarded as minimum, until they taught the next one to their pupils. Mabuni too had this opinion and always recommended quality above quantity.

In view of Shitô-Ryû’s amount of Kata, one has to keep in mind that Mabuni himself never regarded a deep understanding of all these Kata as really important for the mastery of his style. Like Funakoshi Gichin, Mabuni was also an advocate of the ’Hito Kata San Nen’-maxim. Three years constant practise of one Kata was during those days the amount many masters regarded as minimum, until they taught the next one to their pupils. Mabuni too had this opinion and always recommended quality above quantity.

In his book ’Kôbô Jizai Goshinjutsu Karate Kenpô’ he wrote: ”In the past, there were few Karate-jutsu experts who knew many Kata. If you specialize and study only a few Kata, then you will be a serious Karate-jutsu student.“ Elsewhere, in Nakasone Genwa’s ’Karate Kenkyû’, Mabuni wrote: ”If practiced correctly, two or three Kata are sufficient as “your” Kata. All the others should just be studied as a source of additional knowledge. Breadth, no matter how great, means little without depth.“

For Mabuni, the study of Kata always contained not only techniques alone, but also their analysis (Bunkai) and application with a partner (Ôyô). In his Kata-article in ‘Karate Kenkyû’ he wrote: ”[…] Kata must be practiced properly, with a good understanding of their Bunkai meaning.“ Similar to that, he wrote in Seipai no Kenkyû’ unmistakably: ”Kata movement is meant to be used in a real encounter […]“. Most likely also in view of the various possibilities of Kata-Bunkai, he advises the reader in ’Karate-Dô Nyûmon’: ”The technique is infinite, arrogance is undesirable“ .

This unity of form and application becomes apparent in nearly every of Mabuni’s publications.

In his works on Seipai, Seiunchin or Aragaki Sôchin he does not only present explanations on the particular movements, but always also elaborates and fully illustrates the information on their application. In addition to that, the four pictures of his article ’Kumite Kenkyû’ can be easily traced to Shitô-Ryû’s Kata. Mabuni’s statements concerning the application of techniques are as always, especially in comparison to other contemporary publications, very detailed and offer both a remarkable breadth and an astonishing depth.

For example in ’Seipai no Kenkyû’, he not only demonstrates striking (Tsuki-), receiving (Uke-) and kicking techniques (Keri-waza), but also throwing (Nage-), joint-manipulation- (Kansetsu-) and counter-techniques (Gyaku-waza) against locks and grips. Also worthy of mention is Mabuni’s counter against a ‘rear shoulder lock’ (Ushiro-Kata-Gatame) on the basis of the ’Pinan Sandan’-form, which he presents in ’Karate-Dô Nyûmon’. Additionally he wrote in the same work: ”The Kata of Gojû-Ryû contain many interesting throws and joint-locking techniques, which haven’t been taught in Tôkyô. The practitioners of this system should never neglect their study of these throws.“

Mabuni shifted his focus early on in the teaching and research of Karate. Already the foundation of the ’Karate Kenkyûkai’ in 1918 (Taishô 7) [‘Karate Kenkyû Kurabu’ from 1925 (Taishô 14) on] was a novelty and lead to a remarkable association, which incorporated various styles and accomplished a quality of its members, which is still unequalled.

Beneath his enthusiasm in Kata, Mabuni also had a lot of interest in Karate’s ability to be an instrument of physical education.

One of the major targets of his work was also to promote the spread of Karate under the aspect of health promotion, in order to improve the well-being of the general population. Mabuni viewed Karate as an excellent practice of physical education and constantly highlighted this very important aspect. In his work ‘Karate-Dô Nyûmon’, he writes in great depth about the positive influences of Karate-training on body and mind. In co-operation with a medical university he was able to even prove these effects partly by blood- and urine-tests.

Another important cornerstone of his research is the first edition of the ‘Bubishi’ in 1934 (Shôwa 9). This legendary Chinese text has been transmitted over generations among Okinawa’s Karate-masters and has had significant influence on the research and understanding of people like Higashionna Kanryô, Funakoshi Gichin, Itosu Ankô, Shimabukuro Tatsuo (1908-1975) and many others. To Yamaguchi Gôgen (1909-1989) the ‘Bubishi’ was the ”most treasured text“ and Miyagi Chôjun even called it “the Bible“ of Karate.

Mabuni was without any doubt also one of Karate’s greatest visionaries. During a time when women were the excluded absolutely in a Karate-Dôjô, Mabuni developed special concept of self-defense for them. On request of the Japanese government, Mabuni, together with Konishi Yasuhiro and under the assistance of Ueshiba Morihei, devised the Kata ’Green Willow’ (Aoyagi or Seiryû). These special techniques of Mabuni’s Shitô-Ryû and Konishi’s Jûjutsu encompasses and takes into consideration the anatomy of ’the fair sex’. Mabuni’s Kata Myôjo (Venus) is another product of his research in this field, which he even wanted to dedicate a special book (‘Mabuni-Ryû Karate-Dô Kenpô Joshi Goshin-jutsu’) to. Unfortunately this project remained unfinished.

In view of all these accomplishments it is not surprising that Mabuni was held in such high esteem among both Japanese and Okinawan Karate masters.

In view of all these accomplishments it is not surprising that Mabuni was held in such high esteem among both Japanese and Okinawan Karate masters.

In the field of weaponless fighting, he was commonly considered as an “outspoken expert”, as his son Kenei reported later. His Kata-ability was especially well respected. According to his son Kenzo (1927-2005), Mabuni knew altogether more than 90 different Kata.

His other son Kenei indicates an even higher amount, when he says that “70 percent of the Kata” his father “had studied are lost in Okinawa today”. Considering this, Funakoshi Gichin once said: ”If you want to know about Kata, ask Mabuni Kenwa“ and called him “an outstanding Budô teacher“ and “the richest source of Karate-Jutsu technique and information in this era“. Motobu Chôki (1870-1944), one of Ryûkyû’s Kumite-experts said: ”For technique, there is none better than Mabuni Kenwa“. In public he was just known as “Mabuni the Technician“.

Mabuni’s outstanding dedication attracted both respect and a grudging respect. Because of his pleasant nature and his remarkable dedication to the art of Karate, it was difficult for others to really hate or discredit him. ”Mabuni could have easily been a rich man several times over had he ever wanted to cash in on his popularity. He was liked by everyone, perhaps envied by some, but hated by no one.” said Ôtsuka Hironori, founder of Wadô-ryu, once about this.

It is hard to form an opinion of Mabuni’s fighting ability. In contrast to other Okinawan Karate-masters, there are not many reports about altercations in Mabuni’s life. According to Sakagami Ryûshô and Mabuni’s son Kenei, he should have had to use his skills quite frequently during his time as a police man. Kenei also states that his father sometimes worked as a referee at Kake Dameshi, ‘challenge fights’ or ‘exchange of techniques’. These fights usually took place on street corners, in backyards and other public places in the evenings or at night. There were usually witnesses and every technique was permitted. It should be pointed out that these events were primarily power struggles for the sake of the learning, so that “the opponent wasn’t beaten-up mercilessly”. The main idea was to “detect strengths and balance weaknesses”.

According to another statement of Kenei, Mabuni himself would have been challenged frequently to such fights and usually accepted them.

Similar to Funakoshi Gichin, Mabuni was also a strict opponent of free sparring (Jiyû Kumite) in his training. Nonetheless, he evidently experimented quite frequently with different kinds of protective gear (Bôgu). Mabuni also put a lot of emphasis on the practice of prearranged sparring.

Although his main focus lay on the practice and analysis of Kata, Mabuni understood the many shortcomings of training exclusively in Kata for the mastery of Karate.

He wrote in his article ‘Kata wa Tadashiku Renshû Seyo’: “The correct practice of Kata […] is the most important thing for a Karate student. However, the Karateka must never neglect Kumite- and Makiwara-practice.“ If the Karateka however disregards Kata training and concentrates completely on Kumite and Makiwara then this, according to Mabuni, will lead to “unexpected failure when the time comes to utilize your skills”.

In order to get satisfactory results, Mabuni advises to train seriously and spend fifty percent of the training time on Kata and fifty percent on additional practice.

Stay tuned for the last part in the series (pt. 4), entitled Mabuni’s influence on JKA Shôtôkan-ryû

11 Comments