I love mysteries.

Do you?

I’ve watched CSI, Law & Order, Midsumer Murders, Prison Break, Lost and other TV shows involving mysteries more than anyone in their right mind should be allowed to.

Need I mention I’ve read all of the books on Sherlock Holmes too?

It’s something about these mysteries that grabs hold of me, and my guess is that’s why I am so interested in kata.

Because, though it wasn’t always so, today a kata equals a mystery.

A secret enigma wrapped in a riddle trapped in a puzzle inside of a cryptogram. With some question marks sprinkled on top.

At least if you look deeper than the “shell” of a kata, which sadly seems to be the popular way of “studying” a kata today.

Now, without seeking – in any way – to denigrate the apparent hardships of performing and mastering a kata in its mere physical sense, which I know is no easy task, I truly believe that narrowing oneself to the sheer outward appearance of kata is a big mistake for the person seeking to eventually, maybe, perhaps, one day master Karate, since the underlying principles of kata (and, of course, Karate in whole) lies in gradually exploring the depths of it’s many layers, which means studying not only the ‘sword’, but also the ‘pen’, to put it in Western terms.

As Mabuni Kenwa so nicely put it in his essay entitled “Practice Karate Correctly”:

“Breadth, no matter how great, means little without depth.”

And perhaps the best kind of “depth” is found in books.

Books, books books.

I actually got two books just ten minutes ago, in my mail. They’re right here besides me. Nothing special, just some “Neuromuscular Efficiency and Biomechanical Sports Specific Quasi-isometric” kind of stuff. You know, the usual.

However, according to studies, the typical American buys precisely one book a year.

Ouch.

Of course there are a lot of Americans who buy zero books each year too. And then there are people like me who buy 400 (though I’m no American).

This is a problem.

Because we need knowledge if we are to solve this whole kata thing. You know, the mystery we talked about in the beginning. Bunkai and all of that.

So, to show you that not all of my knowledge gained from books is useless (“Did you know that Napoleon’s favorite horse was named Marengo?”) I actually have a real-life practical example for you today. An example of how I once read a book on one thing, and later read a book on another thing, and then connected the dots somehow, ending up with a nice solution to my problem at hand.

Here’s what happened:

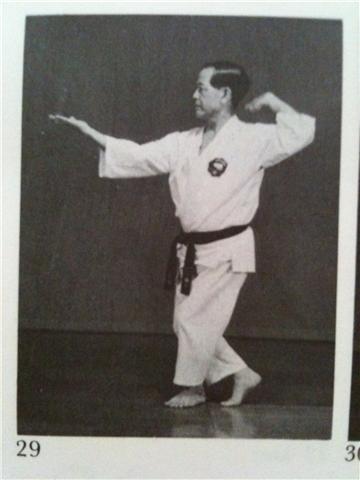

One cold winter day I was thinking about an application for the popular move we see right here, found in the kata Kusanku/Kushanku/Kosokun/Kanku (or whatever your organization thinks the pronounciation should be):

Looking at the stance (zenkutsu), the possible hand techniques (nukite, shuto etc.), and the preceding and following techniques (maegeri etc.) didn’t give me that much useful. I had many ideas to the application, but nothing better than the plethora of standard bunkai you’ll find on Youtube.

So, I forgot about the issue for a while concentrating on other projects.

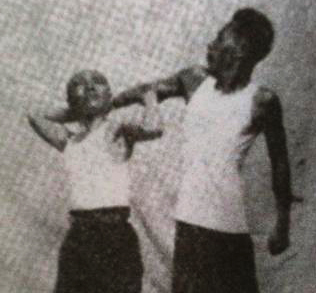

Then, one day, I was reading an interesting book on traditional Chinese submission grappling (Chin-na) from 1936, casually flipping through the pages, when I suddenly came to the following move:

The book called it “Lifting the elbow” and said it was an elbow lock, in defense against somebody grabbing your hair from behind.

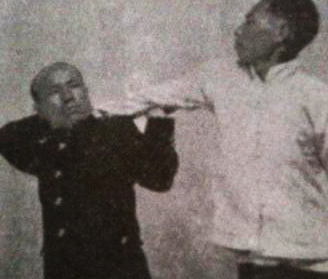

There was another version where your collar was grabbed from behind too:

To me, this was the key.

This was the bunkai to the move I was looking for!

I had what some people refer to as a “blinding flash of the obvious”

“But hey, Jesse-san, have you gone blind? It doesn’t look at all like the move from the kata! The back hand should be in front of the forehead!”

No, that’s right. It doesn’t look the same.

But that’s when I remembered another thing I had read (and seen too, plenty of times).

The thing is, in the old Shorin-ryu version of Kusanku (that everyone in Okinawa practises), the move looks exactly like this.

See for yourself:

You spin around to face the opponent (hence the kosa dachi) grab the hand behind your head (hence no hand in front of the forehead) and lift up the elbow of your opponent, trapping him/her in an elbow lock (hence not a shuto-uchi).

- Without an opponent; it looks like the picture above.

- With an opponent; it looks like the two pictures above the picture above.

Does it get any more obvious?

My “mystery” of a bunkai had been solved by flipping through a book on Chinese submission grappling from 1936, and subconsciously (?) connecting that to the above picture that I’d seen in Nagamine Shoshin’s “The Essence of Okinawan Karate-Do”, while at the same time keeping in mind that the modern Kusanku move in question derives from the above picture which represents the old Shorin-ryu version.

Case closed.

The bunkai was found.

And you have no idea how many times I’ve discovered things like this in the exact same fashion.

By reading books.

By looking at videos.

By questioning, searching, learning and finally remembering.

Sometimes it’s simply “Elementary, my dear Watson.” as Sherlock himself would have said.

8 Comments