At the age of 14 or 15, I was standing in a half empty hallway in my junior high school, talking to a classmate.

He had a problem.

The problem was, my friend had written an essay that our teacher didn’t like.

I don’t remember what it was about, but it was not very good. So he asked me how to improve it. (Not that I was an expert, but at least I had higher grades than him.) So, I gave him a short lecture on what I thought constituted a good essay.

I don’t really remember, but I probably said stuff like “You will need a catchy beginning, spell everything right, use punctuation” and such.

Coincidentally enough, at the middle of our conversation our teacher happened to walk by.

Or maybe I should say sneak – we hadn’t really noticed him.

But we sure did, when he suddenly exclaimed: “No, that’s wrong!”

(He was a dramatic man.)

I turned around with a surprised look on my face – and yes – he was talking to me.

“What is he talking about?” I thought.

All I knew was that I had just told my friend that his essays would be better if he would just throw in some more cool adjectives. You know, instead of writing phrases like “a summer day” he could use “a magnificent azure blue sky” and “the luscious aroma of flowers” or something.

And that’s what my teacher didn’t like.

He had overheard me.

But I didn’t understand what he meant. Come on, who doesn’t love adjectives? They can make even the most spartan text look ridiculously advanced and professional!

Here’s what he told me:

“Listen, Jesse, adjectives are for beginners! Look at the greatest writers in history, they never used more adjectives than necessary. And they always chose them carefully. What makes a good story great is that it forces the reader to imagine for himself. It makes the reader use his own fantasy!

If you tell the reader everything, then they have nothing left to imagine!

And that would be a truly boring piece of work!”

Whoah…

That turned my world upside down. My teacher had totally flipped the script, giving me a lesson I was never to forget. You see, my idea had always been that the more words you use, and the more creative you are in combining these words, the better your text will be!

But now I was told the complete opposite.

I was told to discard all fluff, and let the reader do the work in his own mind.

To draw a parallel, it’s the exact same thing as if you would see a movie based on a book. In 9 times out of 10, the book is always better than the movie, right? Why? Because the movie is not how we imagined it.

The movie is just how the director happened to imagine it.

So, though my classmate has probably forgotten all about the lesson I told him that day in junior highschool, I’ve never forgotten the one I got.

“Less is more”.

And this holds equally true for everything from writing to designing. From cooking to painting.

Even for martial arts.

And yes, for Karate.

Maybe Bruce Lee summed it up the best, when he told us that we need to “Hack away at the unessential.”

And this is also what “Hick’s Law” tells us.

According to sensei Wick E. Pedia, Hick’s Law (named after British psychologist William Edmund Hick) describes the time it takes for a person to make a decision as a result of the possible choices he or she has (just for the record, the original Hick’s Law goes TR+a+b{Log2 (N)}).

This is über important when speaking about martial arts, where response time not only determines who is the winner and the loser (sports), but possibly even who is the survivor… and whatever word the opposite of a survivor should be called.

Body bag?

Theoretically, the fastest response time a human being can have is if there is one stimulus and one response choice. This means one attack, one defense. Very simple. If we add more choices, we slow down response time.

Likewise, if we add more stimuli, we also slow down response time.

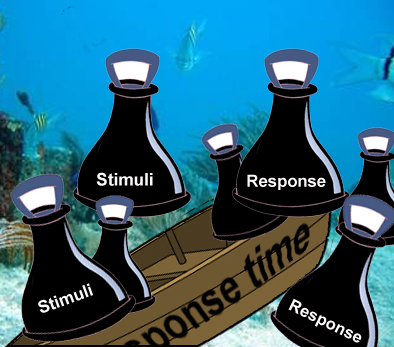

You could think of it as a boat:

This is optimum performance for the boat.

Using a straight punch as an example, in this case we are attacked by one type of straight punch, and we know exactly one way to defend against this straight punch.

Perfect.

We will react as quickly as my old neighbour (an elite computer nerd) did when he got the newest Logitech G7 Laser Cordless Mouse.

But…

Bad guys don’t go around using exactly one type of attack, with the same arm, at the same height, on the same target, same trajectory, with the same amount of force. Do they?

No, they use different types of attacks.

The possibilities are almost endless. And what are your chances of successfully dealing with all of these different attacks? Let’s look at that boat again.

Add more weight (on either side of the boat), and the response time changes drastically, as illustrated below:

(My photo editing skills just reached new hights by the way)

Adding either stimuli (a different kind of attack) or response (a different kind of defense) makes our reaction time sink to the bottom. System overload.

And suddenly, quotes like “In our dojo we know three hundred thousand defenses against the straight punch” makes you just shake your head and ask one thing:

“Why?”

Because, as Hick’s Law tells us, for every extra defense (reaction) that we learn for a certain attack (action), we effectively hinder our own chances of coming out on top of the encounter! It is a fact that the fewer variations of a response that we drill, the more effective (and possibly more boring) our training will actually be.

Which leaves us with the paradoxical conclusion that:

- The more techniques you know…

- …the less likely you are to successfully use them.

Ultimately, the best system is the one that relies on teaching principles.

Kicking, punching and blocking are no more Karate than a knife, fork and spoon constitute dinner. These are simply aids, or tools, for understanding and imparting the principles that justify and govern their whole existence.

And that’s what Karate should be about.

Less.

Not more.

4 Comments