July, 1921.

World War I is officially over.

Japan’s economic bubble is exploding.

To keep people from thinking about the imminent postwar recession, the Japanese government decides to boost public entertainment.

As we all know, media is the best medicine for a harsh reality, right?

One day a special program is shown in cinemas…

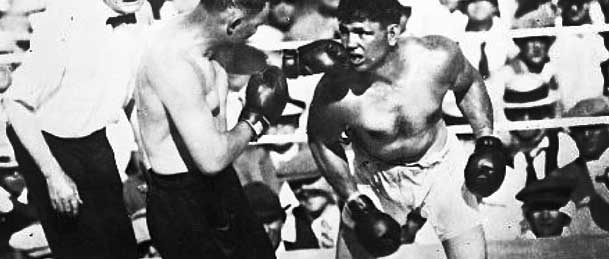

It’s the world championship in boxing, between Jack Dempsey and Georges Carpentier.

Many Japanese people had never seen boxing like this before.

They were AMAZED!

You see, in Japan, they traditionally used weapons for fighting – like the long/short sword, bow & arrow, spear or knife. If they didn’t use weapons, they fought using wrestling, throws, sweeps, joint locks, chokes and so on.

Fighting like these Western boxers did was insane!

Japanese martial arts didn’t have anything like it.

What an incredible opportunity…

The Japanese leaders noticed people’s reaction to boxing and saw this as a brilliant chance for strengthening the nationalism and unique Japanese spirit (yamato damashii) of its citizens.

Famous boxers would be invited to promote the sport in Japan. Public demonstrations would be held. Boxing clubs would open and exciting boxing matches would be broadcasted around the nation.

This would boost the samurai spirit of Japan!

There was just one small dilemma:

Not all people liked the idea of bringing in more foreign influences.

The Japanese school system, military model & infrastructure was already based on European influences, particularly from Germany, Great Britain & France.

Couldn’t some Japanese people teach boxing instead?

Well, believe it or not…

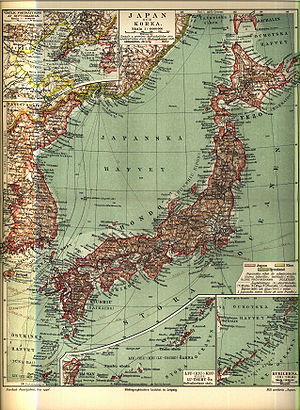

In 1921, a Tokyo magazine published a groundbreaking article by Sasaki Gogai, who told the Japanese public that they shouldn’t look to the West for foreign experts of fistic traditions, as they themselves possess such skills in an island kingdom to the south.

That island was Okinawa – the birthplace of Karate.

The same year, crown prince Hirohito had visited Okinawa on his way to Europe. During Hirohito’s visit, a demonstration was given in his honor by a group of local performers.

The cultural show included dancing, singing, live music…

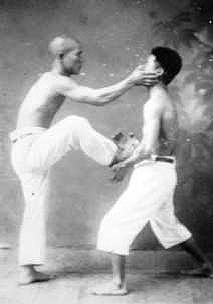

…and something called “Toudi”.

Toudi was the name of the local martial art in Okinawa. The name literally meant “Chinese Hand”, signifying that it was influenced by ancient Chinese fighting arts.

The demonstration involved a variety of strikes, kicks, blocks and punches against opponents, as well as fighting without opponents – like shadow boxing.

Unbelievable.

This rural fighting art, from the tiny island of Okinawa, could indeed become the answer to boxing that the Japanese were looking for!

One of the performers was the perfect man for spreading Toudi to mainland Japan. He worked as a school teacher, was educated, spoke good Japanese and had practiced Toudi since young age.

His name was Gichin Funakoshi [1868-1957].

(Or Shoto, as he liked to call himself.)

He became “the chosen one”.

In May 1922, Gichin Funakoshi was invited to the 1st National Athletic Exposition held in Tokyo’s Ochanomizu district, to promote Toudi.

His presentation was a hole-in-one!

Everyone in mainland Japan loved Funakoshi’s stuff, and convinced him that his skills were much needed in times like these. He could now complete the quest of his teacher Itosu Anko, who years earlier had spearheaded a campaign to popularize Toudi in Okinawa via the school system.

Funakoshi could bring Toudi out from its cradle, make it an official Japanese martial art and honor the legacy of his master at the same time.

Aaaaaaw yeah!

To help him, a man named Jigoro Kano offered his support.

Kano was the founder of Judo. He had gone through a similar process of modernization himself (Judo was created from Ju-Jutsu) and knew that his mentorship would be needed for Funakoshi’s upcoming task.

This proved to be 100% correct.

(In fact, Funakoshi’s students later recounted that their sensei would frequently remove his hat and bow on the street outside of Kodokan, the headquarter of Judo, to show his eternal gratitude for Jigoro Kano’s invaluable help.)

Now, here’s where things get interesting…

Since Japan was a culture of conformity, Toudi had to undergo a number of radical changes to become accepted as an official martial art and fit in with the other Japanese martial arts of the time; like Judo, Aikido, Kendo, Iaido etc.

For example, the name had to be changed.

You see, the Japanese hated everything with connections to China. To practice a martial art named “Chinese Hand” was politically out of the question.

In 1933, the name was officially changed to “Karate-Do”.

“The Way of the Empty Hand.”

(Related reading: 10 Differences Between Okinawan Karate & Japanese Karate)

And that was just the tip of the iceberg.

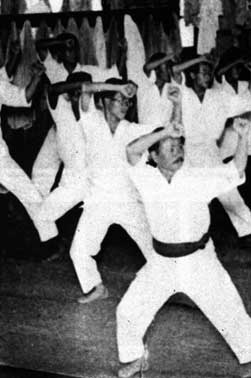

Everything became systematized, codified and formalized.

Everything became systematized, codified and formalized.

Ritualized acts and Japanese terminology were introduced, along with a belt system, kyu/dan ranks, uniforms, new techniques, simplified movement patterns, the shift from self-defense to character development, tournament rules, new kata names, safety regulations and more.

This was the birth of modern Karate.

But Funakoshi wasn’t alone in this.

Every Okinawan Toudi practitioner who came to Japan, including pioneers like Miyagi Chojun, Mabuni Kenwa, Motobu Choki, Kanken Toyama, Taira Shinken, Uechi Kanbun etc. had to conform to these new rules.

Like the Japanese saying goes; “deru kugi wa utareru”.

(“The nail that sticks out gets hammered down.”)

During this period, the concept of “styles” was also invented.

The reason was simple: If your Karate looks different from my Karate, they can’t be called the same thing, can they? Therefore, every sensei had to register a name for his “style” with the Dai Nippon Butokukai (Greater Japan Martial Virtue Society).

A new type of instructor license was also invented, called “renshi”. This was done mainly to avoid awarding Karate teachers any pre-existing titles like shihan, kyoshi or hanshi, as they were considered too noble for common island people.

This is where Karate became BROKEN.

Let me explain why:

Remember how I wrote that Karate was seen as a Japanese alternative to boxing?

There was just one problem…

Toudi was a complex fighting art comprised of strikes, kicks, punches, blocks, grappling, throws, joint locks, ground techniques, escapes, counters, pressure points, weapons and much more.

But the Japanese didn’t need all this!

They already had those things in their own martial arts (collectively known as ‘Budo’).

So they decimated Karate’s technical registry.

Karate was ruthlessly pigeonholed to satisfy the needs of contemporary Japanese society and political agenda.

The meat was scraped off the bones, and neatly packed in a 3K format:

Kata, kihon, kumite.

This is why many Karate practitioners lack the ability to handle real-world situations.

The limited arsenal of modern Karate simply doesn’t empower the average Karate enthusiast with the skills to address its original purpose (civil self-defense) anymore.

Kenwa Mabuni, a friend of Funakoshi, admitted this later:

“The Karate that has been introduced to Tokyo is actually just a part of the whole. The fact that those who have learnt Karate feel it only consists of kicks and punches, and that throws and joint locks are only found in Judo or Ju-Jutsu, can only be put down to a lack of understanding […] Those who are thinking of the future of Karate should have an open mind and strive to study the complete art.”

– Kenwa Mabuni [1889-1952]

So…

Is all hope lost?

Are we doomed to studying an incomplete martial art?

Definitely not!

The original Karate techniques are not “lost”.

They are still here – hidden in plain sight.

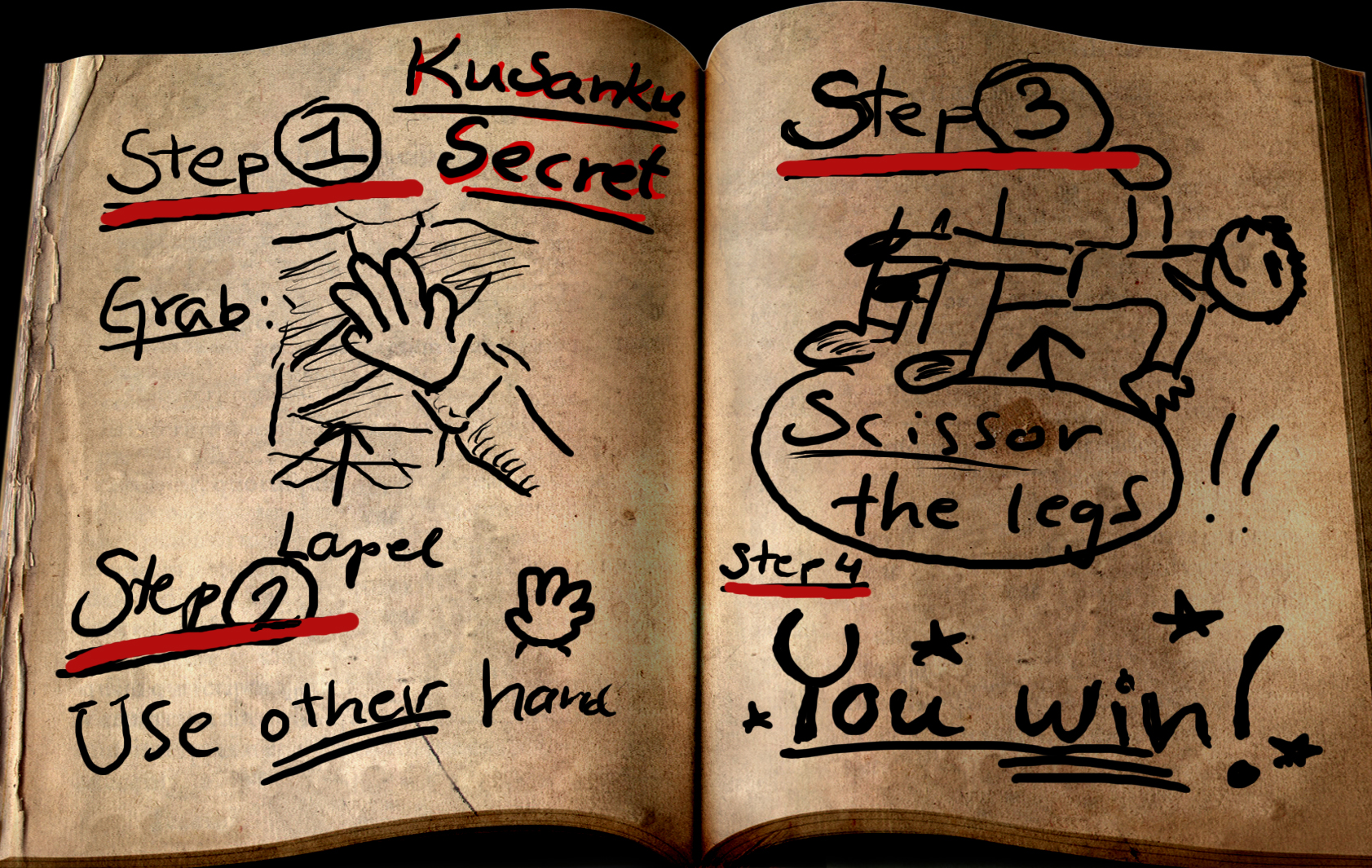

Embedded in conceptual time capsules known as KATA.

And the key to revealing their secrets is spelled:

B-U-N-K-A-I

You see, kata still contains the essence of how Karate was originally meant to function.

(Related reading: The Bunkai Blueprint: A Simple Framework for Applying the Kata of Karate in Practical Self-Defense)

That’s why the traditional saying “hito kata, sannen” (“one kata, three years”) holds so much weight with Karate practitioners who strive to extract the practicality hidden in kata.

Karate was a complete art.

You can make it whole again.

Understand kata to understand Karate.

Your link to the past is your bridge to the future.

Bring the essence back!

_________

Big thanks to Patrick McCarthy, the world’s #1 Karate researcher & author, for providing me with the historical insight presented in this article. Check out his new edition of Bubishi: The Bible of Karate, where I had the honor to contribute the prologue.

77 Comments